|

From ACIG.org Central and Latin America Database

Costa Rica has got its current name from the times of visit by Christopher Columbus, in September 1502, on his fourth voyage to the Americas. Noting that some of the natives wore gold decorations, Columbus dubbed the area “Costa Rica” (Rich Coast), imagining that there must be a rich empire lying further inland. The Spanish King Ferdinand appointed Diego de Nicuesa as governor in 1506, but the colonialisation was hampered by the jungle, tropical diseases, and the Indian insurgency. Through the 16th and 17th Century, isolated from the coast and major trading routes, Costa Rica was barely surviving as a “forgotten” Spanish colony. The situation changed only slightly in the early 18th Century, when new settlements were established in the fertile central highlands. In the 19th Century, Costa Rica was briefly a part of the Mexican Empire, before joining the United Provinces of Central America, and then declaring itself independent under President Juan Rafael Mora. For the rest of that century the country slowly became coffee exporter and saw an economic and cultural growth: as some of the agricultural entrepreneurs became rich, a class structure developed. In June 1855 the American filibuster William Walker conquered Nicaragua, intending to convert the area into slaving territory and use it to built a canal joining the Atlantic and Pacific. Under the threat, President Mora mobilised 9.000 civilians into an Army that marched north and defeated Walker, forcing him to flee. Subsequently, in 1889, Costa Rica became one of the first Central American democracies, and the democracy have been a hallmark of the country – which became known as one of the most peaceful nations in the world – ever since. It was only for a very short period in the 1940s and 1950s that the situation was different. The dominant figure of the Costa Rican political life in the 1940s was Jose Figueres Ferrer, better known as “Don Pepe”. A charismatic man, Don Pepe was an agricultural entrepreneur, and economist, politician and philosopher. A moderate socialist, Figueres had spoken against the government fraud and corruption in a radio show in 1942: he was apprehended before ending the transmission and sent to exile in Mexico. There, he started plotting the military take-over of the Costa Rica, accusing the government of President Rafael Calderon Guardia. In 1944 two intellectuals, lawyer Rodrigo Facio Brenes, and historian Carlos Monge Alfaro, joined him, and formed the party called “Partido Accion Democrata”, reorganized as “Partido Social Democrata”, in 1945. Over the years, Don Pepe and his followers were signing a series of agreements with other Latin American countries, according to which he was to receive arms and support in exchange for Costa Rica becoming a platform for destroying dictatorships in the area. Once this agreement was signed, in 1947, Don Pepe started training local and foreign militia. After elections in 1948, President Picado declared the election of Otilio Ulate a fraud and refused to step down from his office. Don Pepe saw this as a perfect opportunity to launch his attack, camouflaging the civil war as a reaction against a violation of a democratic process. Don Pepe’s forces launched an invasion, causing a civil war that lasted for five weeks and took the lives of 2.000 people, mostly civilians. A cease-fire was negotiated by the diplomatic corps: Picado’s and most of Calderon’s followers surrendered in exchange for the pardoning of their lives and respect of their properties. Don Pepe, however, did not honour his agreement, but persecuted his enemies, closed down the Communist Party, and took over several properties that belonged to Picado, Calderon and their followers. Supported by a military junta, he remained in power for 18 months, establishing important institutions – placing banks under national control, for example – and reforms, including giving women the right to vote and providing full citizenship and rights to the black population of Costa Rica. Don Pepe stood to his promise, and after 18 months in power he passed on the office to the winning candidate – President Otilio Ulate. Ironically, one of Pepe’s and military junta’s final decisions was to disband the army and replace it by a 4.000 strong National Guard. Thus the Civil War of 1948 resulted in a peaceful and reformist outcome – in stark contrast with the fate of many of Costa Rican neighbours, all of which suffered extremely long and brutal dictatorships. Don Pepe returned to power in 1953, after being elected President again. By the time, Rafael Calderon Guardia was gathering his remaining followers (“Calderonistas”) into an armed force based in Nicaragua, where they were supported by dictator Anastasio Somoza, who claimed that Don Pope participated in a plot to assassinate him. By late 1954 the Calderonistas gathered a relatively well-armed force of some 200 (according to contemporary Costa Rican press), which operated one Republic F-47D Thunderbolt, two Douglas C-47s, and two North American AT-6 Texans. These aircraft were based in Managua and sold to Calderon by the Interarms company, of well-known arms dealer Sam Cummings - together with a number of WWII-vintage Vickers "Universal Carriers". On 11 January 1955, Calderon led his force down the Pan American Highway into Costa Rica and seized the northern border town of Villa Quesada, near the coast of Pacific. Figueres immediately appealed to the Organization of American States (OAS) for help. While waiting for the OAS commission to provide its report about the rebels and who was supporting them, the Costa Rican President was forced to mobilize the Costa Rican National Guard, and armed it with weapons purchased (also) from Interarms. Simultaneously, a single DC-3 was borrowed from an airline and armed with two 0.30in machine guns. This was hardly adequate, especially since on 13 January, Jerry “Fred” De Larm – a mercenary flying F-47D for Calderonistas – flew a strike against civilian targets in San Jose. On the same day, De Larm’s F-47D and two AT-6s also strafed some of National Guard units that were advancing on Villa Quesada, which was put under attack already since 05:10hrs in the morning. By 08:00hrs, after suffering a loss of three killed, the rebels pulled out. On the following morning the OAS commission’s report was published, according to which the rebel’s supplies and war material were from Nicaragua. As soon as this became known in the public, Somoza ceased supporting Calderonistas. But, by the time an armed conflict was inevitable.

On 18 January a National Guard unit of 45 attacked rebel positions near Hacienda Santa Rosa, causing the Calderonistas to counterattack with two AT-6s and one of their DC-3, which was equipped with light-machine guns, mounted in the cargo doors. The Costa Ricans returned fire and claimed the DC-3 as shot down (its wreckage was subsequently found in the bush north of the city). In the following battle on the ground, several National Guards were injured, including the local commander, but by the noon of 19 January the rebels were forced to flee into Nicaragua, leaving 15 killed as well as a considerable amount of arms, ammunition and equipment (including at least a single Vickers Universal Carrier). On their retreat they suffered additional losses in firefights near Cruz de Piedra, and then near La Cruz. By that time several commercial aircraft pressed into service by the National Guard were used to pursue and attack them even behind the border.

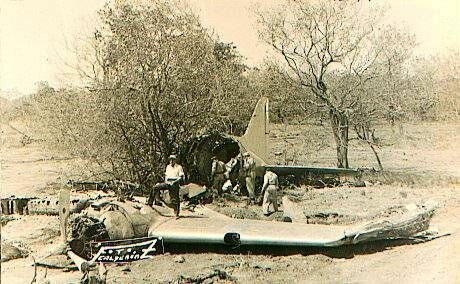

Nevertheless, meanwhile the OAS requested urgent help from the USA and four North American F-51D Mustangs – former mounts of the 182nd FS, Texas Air National Guard – were sold to the Government for a nominal $1 each. The Mustangs were left in “bare metal” overall, and given only basic national colours – the Costa Rican flag - as insignia on fuselage and wings: Costa Rica never had an air force, and there was no official air force insignia. In addition, the aircraft have got serials 1 thru 4 on fuselage, while keeping their US-serials on the fin. They were based at Las Canas and flown by only three pilots – at least two of which were said to have been mercenaries as well: Coronel Fernando “Muneco” Araya, Manuel “Pillique” Guerra, and Johnny Victory. To which degree were Costa Rican Mustangs deployed in combat remains unclear, then it is unclear if they became operational by 22 January, when the Government declared the “invasion (for) eliminated”. It is only known that immediately upon their arrival, on 19 January 1955, the F-51D 44-733339 was written off in an accident. De Larm later claimed to have actually shot down this Mustang in a dogfight, but his claim was never confirmed, even if it is likely that the Calderonista “air force” remained active even in the days after the defeat at Santa Rosa.

The three other Mustangs, including 44-74978 and 45-11386, continued to support the National Guard in the following days. While some heavy fighting occurred in several towns, the insurgents proved no match for the popularly backed National Guard and were swiftly driven back over the border into Nicaragua. The tensions decreased already by March 1955, and in early 1956 Costa Rica and Nicaragua finally agreed to cooperate in surveillance of their border. The Costa Ricans operated their Mustangs only for a while longer: on 22 January 1956 the F-51D 45-11386 was lost during a celebration flypast. Of the last two Costa Rican Mustangs, one was re-imported back to the USA, in the 1970s, and given spurious Costa Rican markings as well as the title “El Gato Rapido” (Fast Cat). This feature was adopted from corresponding chapter "11.7 Costa Rica, 1948-1955", in the book "AIR WARS AND AIRCRAFT; A Detailed Record of Air Combat, 1945 to the Present", by Victor Flintham, Arms and Armour Press, 1989 (ISBN: 0-85368-779X) Additional details foremost from the website El Espiritu Del 48

© Copyright 2002-3 by ACIG.org |