|

From ACIG.org Former USSR-Russia Database

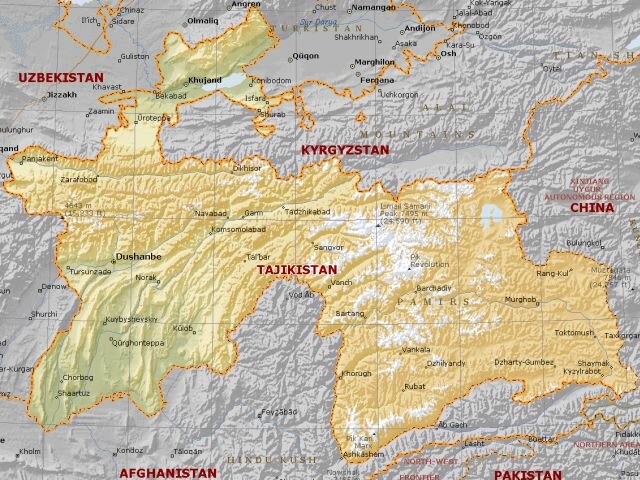

Tajikistan is situated at the crossroads of major Asian civilisations – Chinese, Indian, Persian, Russian and Turkish, and was influenced by all of them. For this reason the conflict in this country was one of potentially most dangerous of all the wars in the former USSR: it erupted as a result of a strife between reactionary post-Communists and Islamists, and could easily spill over into several neighbouring countries. The danger of such an escalation was even larger due to the fact that a number of foreign powers became involved, each of them searching to satisfy own interests. China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan were concerned about the spread of Islamic fundamentalism: therefore, they supported Tajikistan’s post-Communist, secular regime. Russia additionally was concerned to safeguard the 90.000 ethnic Russians living in the country, as well as own troops deployed there, while Uzbekistan attempted to safeguard the 1.5 million ethnic Uzbeks. Pakistan and Iran were interested in reinforcing the Islamic and Persian identity of the locals, respectively. Tajikistan is a land-locked, mountainous country, bordering to Afghanistan, China, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan, with population of 6 million mainly consisting of Tajiks (65%), Uzbekhs (25%), and Russians (3.5% including Russian-speaking nationalities). Some 70% of the population lives in rural areas, often in pitoresque towns and villages, hidden in the shade of towering mountains around them. Capital is Dushanbe, an ancient city with a very specific mix of architecture. The official language is Tajik, a dialect similar to Farsi (Persian language), but much of rural population speaks Uzbek as well. Tajikistan is made up of a number of distinct and isolated regions, most of which are more closely linked economically to neighbouring countries than to each other: in between are high mountains, the eastern end of which consists of the Pamir range, the foothills of the Himalayas. Dushanbe is in the Hissar Valley, where most of the country’s hydroelectric facilities and industry is situated. Majority of the population is concentrated in this area, yet the northern part of Tajikistan – the so-called Leninabad Oblast, with local capital Khojand, in the Fergana Valley, which is tightly integrated with Uzbekistan – is the most industrialized and developed area. Other areas are Kulyab and Kurgan-Tyube, distinct for cotton production, and Garman and Gorno-Badakhshan, the poorest and most isolated regions.

The fighting in Tadjikistan was in looming already in the mid-1980s, when time and again the Afghan and Tadjik fighters trained and equipped by the Pakistani Inter-Service Intelligence (ISI) were crossing the Soviet border to attack local installations that supported the war in Afghanistan. Interested in reinforcing the Islamic identity of the locals, and in cooperation with CIA, the Pakistanis launched a small-scale campaign in which thousands of Qorans – but also some weapons and demolition devices – were supplied to the locals, some of which were then recruited to either fight in Afghanistan, or attack local Soviet installations. After a warning from Moscow to Islamabad that such operations were seen as mingling into internal Soviet matters, the ISI stopped operating inside the USSR, but by 1987 the Afghan Tajiks have already established good relations to their brothers in Tajikistan and ever-increasing amounts of weapons were arriving in the country. The Tajik Soviet Socialist Republic gained independence from the Soviet Union on 9 September 1991, following a coup in Moscow, and became the Republic of Tajikistan. The fighting in Tajikistan begun by numerous killings of ethnic Russians – foremost locally-based soldiers – and violence in Dushanbe between the forces loyal to Emomali Rahmanov, the former Speaker of the Parliament and later the President of the Republic, and a range of opposition parties on the other side. In May 1992 an attempt of the Communist president Nabijew to form a multi-party government failed. The Islamic opposition then seized power from the Tajik Supreme Soviet in a coup, forcing the post-Communists to leave the country. One of the first results was an exodus of local Russians that eventually saw almost nine tenths of ethnic Russians leaving the country. Moscow could not tolerate this situation, and President Yeltsin immediately ordered a military operation, which was to be set so to appear as if there was an internal uprising of forces loyal to the former government. For the following action the Russians mobilized the 201st Motor-Rifle Division, deployed in Uzbekistan, and some 5.000 troops of the “Border Guards”, which were already deployed inside Tajikistan and controlling strategically important sites along the border to Afghanistan. Additionally, in Termez, in the neighbouring Uzbekistan, the Russians established the 1st Brigade of “People’s Front”forces. This consisted of Tajiks from Kulyab and Kurban-Tyube, in the Uzbekh-dominated Hissar region, crash-trained by the members of the 201st Motor-Rifle Division and armed from enormous weapons depots left behind from the USSR-times. This was to become the first unit of what is today the military of Tajikistan. Further, smaller units were organized from local militias, especially from the Leninabad area. Simultaneously, Moscow ordered its Border Guards to prevent the flow of arms from Afghanistan to Tajikistan, but in fact these were doing almost nothing. Consequently, the Islamists had no particular problem in establishing unhindered supply routes. Although the Islamists were not particularly well organized or united – foremost due to different interests of groups from various parts of the country – they soon had a militia of some 5.000 fighters, mainly concentrated in the Dushanbe area, and were also supported by the Afghani Hezbi-e-Islami party of Gulbuddin Hekmatyar.

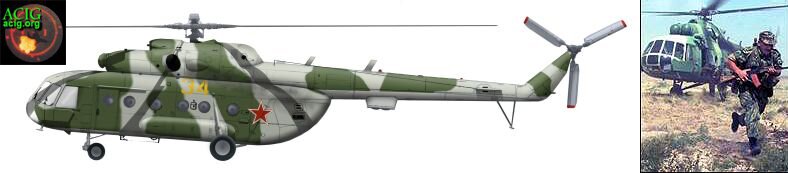

The fighting was bitter and fierce right from begin, and devastated wide parts of Tajikistan, forcing some 70.000 civilians to flee to Afghanistan. Despite considerable support from Moscow, in September 1992 Nabijew was forced to resign and Dushanbe came under the control of Islamists. The Russians then gathered the remaining members of the highest Tajikistani Soviet for a meeting in Khodzent, and set up a new government, led by Imomali Rahmanov, former Kulyab regional executive chairman, supported by the People’s Front forces, and traditionalist northern economic elite of Leninabad. This, however, proved incapable in preventing the Islamists from controlling most of the country. Consequently, the 201st Motor-Rifle Division and People’s Front forces launched their offensive on Dushanbe: supported by attack helicopters, tanks and artillery, by the end of September they were already advancing on the capital, reaching its suburbs by early December. On 4 December 1992 the People’s Front forces, supported by Russian Mi-24 helicopters and artillery, entered Dushanbe, which by the time was one of the last Islamist strongholds in the country. Once a bridgehead was established inside the city-limits, the 201st Motor-Rifle Division charged, occupying the most important objects and installations within only a few hours. As the advance continued, however, one of Russian Mi-24s was shot down near Kofarnikhon, some 25km east of Dushanbe, on 18 December 1992. The remaining Islamist fighters retreated from Dushanbe, and by mid-January 1993 the former Communists were in power again. One of their first acts was to impose a state of emergency and request military aid and support from Russia – in turn legitimating the stationing of the Russian 201st Motor-Rifle Division in the country. This caused a new exodus of the local population and this time over 140.000 of people fled to Afghanistan: the meanwhile 5.000 troops of the Russian “Border Guards” contingent deployed in Tajikistan have left them flee unhindered. After the capture of Dushanbe, the government launched a new offensive towards Kofarnikhon, from where some local Islamist counterattacks came. This city fell fast as well, and then Kurgan-Tyube was captured in a two-prong advance by the end of the month. Around this time the first reports of the Tadjik government were published in which it was mentioned that the Islamists were time and again supported by fighter-bombers and helicopters of the Afghan Air Force. No specific details about such operations were released. Since the government subsequently brought the Pamir range under control, and the major concentrations of the Islamists were scattered, however, the situation subsequently calmed down, even if some sporadic fighting continued in remote areas.

In agreement with the UN, on 22 January 1993 the members of what was then called the “Commonwealth of Independent States” – most of the former Soviet republics, including Russia, the Ukraine, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Kyrgyzstan – decided to deploy a 23.000-man strong “peacekeeping” force to Tajikistan. This contingent already included 15.000 troops of the Russian 201st Motor-Rifle Division, reinforced by a single helicopter regiment. In spring of 1993 the Russians also deployed a number of Sukhoi Su-25BMs and Su-25UBs of the former 115. Guards Fighter-Bomber Regiment in Kakaydy, in Uzbekistan. The personnel of the new unit established in situ, the 186. Fighter-Bomber Regiment, was drawn from the Training Centre in Borisoglebsk, and the Regiment was put under a direct control of Moscow. The Su-25s were soon in the air over Tajikistan, flying combat-air-patrols (CAPs) armed with up to six 250kg-bombs, two R-60/AA-8 Aphid air-to-air missiles (AAMs) and two FTB-800 drop tanks. Also at Kakaydy was the 61. Interceptor Regiment of the newly-established Uzbekistan Air Force, equipped with almost 40 MiG-29 fighters. Initially, the Russians were less concerned with fighting the Tajik Islamists, and more with training additional units of the Tajik Army, which meanwhile grew to over 10.000 troops and became involved in a series of campaigns in the Pamir range, as well as in Garm and Komsolabad areas. It was during the fighting near Komsolabad, in May 1993, that Su-25s of the 186. Fighter-Bomber Regiment flew its first combat sorties. Operational tempo increased from 24 June: during the following few weeks the Su-25s were dropping up to 80 tons of bombs per day. This intensive airborne support was not sufficient to grant destruction or advance of Tajik troops on the ground. The retreating Islamic guerrilla destroyed a number of bridges and roads over mountain passes, and thus completely prevented the government from establishing control in eastern and southern Tajikistan: eventually, a front-line established along the Vanch River effectively splitting the country in two. By the time the UN estimated that up to 70.000 were killed during the war.

By 1994 the Russians still had some 15.000 troops in Tajikistan, mainly deployed in the Dushanbe and Kofarnikhon areas, but frequently deployed along the Vanch River as well. Part of these became involved in the process of establishing the Tajik Air Force, equipped with some ten Mil Mi-8MTBs and five Mi-24s, supplied already in 1993. On the Dushanbe airfield also a full helicopter regiment of Russian Army, equipped with Mi-8s and Mi-24s, was stationed, some of which also operated from the forward site in Kurgan-Tyube. The Tajik Army meanwhile grew to over 20.000 troops, but was still involved in quite intensive operations against the Islamists: several times when Russian troops were supporting such attacks, they suffered quite serious losses. The Russian Border Guard Force (RBF) was meanwhile reorganized as well, now consisting mainyl of Tajiks and other Central Asians, under command of Russian officers. The Islamists, on their side, were not quiet either. They were reinforced by addition of Shi’a militias from the Pamir area and eastern Tajikistan, and reinforced by shipments of weapons from Afghanistan, including some armour and artillery. By 1995 they were ready for the “next round”. On 7 April 1995, when Maj.Gen. Chuyrullajev became the Minister of Defence in Tajikistan, the government intended to declare a ceasefire. Nevertheless, on this day the Islamists ambushed a Russian convoy underway near Kalashum, some 200km east of Dushanbe, and killed 29 Russian troops. Simultaneously, the rebels attacked and overrun the base of the 201st Motor-Rifle Division in Badakhashan, forcing the commander of the unit – Lt.Gen. Chechulim, to order an immediate counterattack. This began by a series of strikes flown by Russian Mi-8Ts and Mi-24s, during which mainly unguided rockets were depoyed. In the following days additional attacks and counterattacks were exchanged, resulting in considerable losses on both sides. Eventually, on 11 April the Su-25s of the Russian Air Force launched air strikes even against Tajik bases up to 30km inside Afghanistan. After these initial attacks brought only insufficient results, on 13 April 1995 no less but 12 Su-25BMs were deployed in a single strike against the city of Talokan, some 50km south of the border to Tajikistan, which was the main base of the Tajik opposition. The Sukhois arrived in two waves, each consisting of six aircraft, and separated by 20 minutes. Deploying cluster bombs, they delivered a tremendous attack – mainly against civilian targets, including the local market: when the locals attempted to help those killed or injured in attack of the first wave, the second wave arrived and dropped even more bombs. Over 100 were killed and 200 badly injured. The Russian High Command denied responsibility for this action, while the regime in Kabul immediately demanded an extraordinary meeting of the UN Security Council. Nothing came out of this. On the contrary, the new Tajik President, Rachmonov requested additional support from Moscow. Despite some resistance from the Russian Ministry of Defence, President Yelzin ordered additional air strikes by the 186. Fighter-Bomber Regiment already on the same day. Consequently, only few hours after attack on Taloqan 12 additional Su-25BMs hit the town of Chach with napalm- and cluster bombs, killing 125. Using an UN-negotiated cease-fire to regroup some of its elements, on 19 April 1995 the 201st Motor-Rifle Division then launched an offensive into Gorno-Badachashan, while a task force of the Tajik Army consisting of a Special Operations Brigade with four battalions and some mechanized units advanced towards the Afghani border. While the Russians advanced for some 20 kilometres into the enemy territory, the Tajik offensive was stopped cold. The matter of fact was that the Tajik Army was meanwhile in a very poor condition and unable to mounting large-scale operations lasting over anything but periods of few days: it had to be permanently supported by Russian and CIS-troops. Consequently, the Russians were forced to fly in several additional battalions aboard transport aircraft to Tadjikistan before the offensive towards the border with Afghanistan could be continued. Eventually, the postponnement was only successful in so far that the Islamists were forced to leave their bases in several valley: their fighting power was not seriously damaged.

The poor condition of the Tajik military was soon to result in unrest from within: in September 1995 the troops of the newly-established 11th Brigade mutinied and had to be fought down by the 1st Brigade, a mechanized company, some special units and even the police. Given additional tensions within other units, and the lack of Russian interest to become even deeper involved in this conflict, the government finally had to give up any large-scale operations. Eventually, with neither side being in condition to reach its objectives or deliver the decisive blow upon the opponent, the fighting died away as the OSCE became involved, deploying observers in Tajikistan and acting as intermediary, initiating the process of national reconciliation. In June 1997 a UN-mediated settlement between the government of Tajikistan and the Islamic-led “United Tajik Opposition” (UTO). Time and again, however, there is renewed fighting as the country is missing almost every deadline set to establish power-sharing according to agreements with both sides. To no small degree it is the Russian and Uzbekistan interests that prevent more positive development of the country, as neither side considers Tajikistan a genuinely sovereign and independent country. In an attempt to make itself independent, Tajikistan signed agreements on trade, economic- and cultural relations with Turkmenistan and Iran. The fact remains that the government of Tajikistan is almost completely authoritarian, even if some nominally democratic structures were established, as well as that the suport base on which the government was established is insufficient for control of the entire country. In 1998 some opposition members were taken into government, and by 1999 the UTO reported that the integration of its fighters into the Tajik military was complete. Consequently, it could be said that at least in the case of Tajikistan the UN and OSCE were successful in negotiating something that appears similar to lasting peace. Nevertheless, most of well-informed observers warn time and again that a new civil war can erupt at any time: sizeable regions of the country remain effectively outside the government’s control, and the differences between different fractions, as well as their inability to organize a functional democracy, remain too massive. The war in Tajikistan can therefore be described as characteristic for its rapid escalation and sudden outbreak, as well as for its relatively quick conclusion through a negotiated settlement. In military sence, sadly, except during its advances on Dushanbe and Kofanikhon, in September 1992, the Russian military failed to show anything else but characteristic - mediocre at best - performance, frequently preferring to target civilians when no viable military objectives were within reach. Despite the successful conclusion of the campaign through negotiations, it is highly questionable if anybody drew any kind of useful concluctions from this conflict. Tajikistan Air Force - ??OVP/Mixed Helicopter Regiment, based at Dushanbe, 20(+) Mi-8MTBs, and five Mi-24s Russian Federation Air Force - 23rd Composite Regiment, based at Dushanbe, equipped with Mi-8s, Mi-24s, An-24s, and An-26s - 186 IBAP/Fighter-Bomber Regiment, based at Dushanbe, Su-25 - 670 BAP/Fighter-Bomber Regiment, based at ?, Su-24M Russian Federation Army Aviation - ?? Mixed Helicopter Regiment, based at Dushanbe, equipped with Mi-8s and Mi-24s Russian Border Guards - Unknown unit, based at Dushanbe, equipped with Mi-8s Uzbekistan Air Force - 60 BAP/Bomber Regiment, based at Khanabad, equipped with 23 Su-24Ms and one Su-24MR - 61 IAP/Interceptor Regiment, based at Kakaydy, equipped with 40 MiG-29s - 62 IAP/Interceptor Regiment, based at Andizhan, equipped with 25 Su-27Ps, and six Su-27UBs Except for own research, to a considerable degree conducted with help of political refugees from Tajikistan, the following sources of reference were used for preparing this feature: - "Afghan Wars; Battles in a Hostile Land, 1939 to Present", by Edgar O'Ballance, Brassey's 1993, 2002, (ISBN: 1-85753-308-9) - Different reports about the war in Tajikistan published in Österreichische Militärzeitschrift: various volumes from years 1993, 1994, 1995, and 1996

© Copyright 2002-3 by ACIG.org |