|

From ACIG.org Europe & Cold War Database

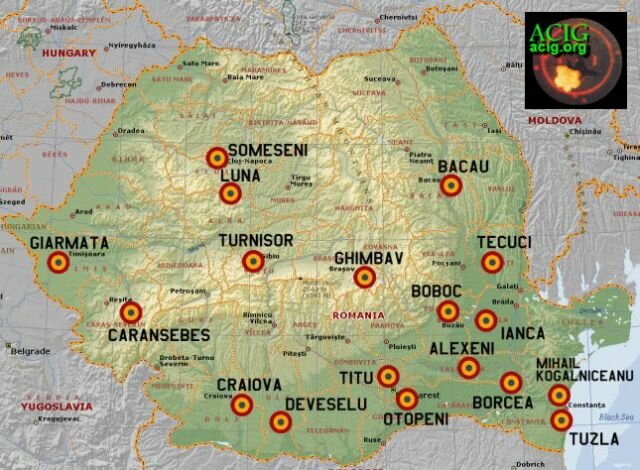

The popular uprising against the Communist dictatorship in Romania, in December 1989, was at the time foremost seen as an act of public unrest and then outburst against a Stalinist dictatorship resulting in fighting between the demonstrants and security authorities in several cities, without – or with only a minimal – involvement of air power. The reality was different, then what happened in Romania at the time was not only an “uprising”, but also a coup – as well as a clandestine confrontation with between various elements of the military, state security, and perhaps the USSR – that saw quite an intensive deployment of the Romanian Air Force (RoAF), and this under very different, often much more difficult circumstances than could be expected. Romania was an important German ally in WWII, but occupied by the Soviets in late 1944. In accordance with agreements of the Jalta Conference, the country subsequently came within the Soviet sphere of influence, and was one of signatories of the Warsaw Pact. In the late 1950s, Romania became the least compliant of the Soviet satellites, and in June 1958, after the country adopted a form of nationalistic Communism quite similar to that of neighbouring Yugoslavia, Soviet forces have left. Since 1963, Romania has asserted virtual independence of the USSR, but relations with Moscow worsened especially since the dictator Nicolae Ceausescu established himself in power, four years later. Subsequently, in some matters, Romania has taken stands in direct opposition to Soviet policy, as in its continuing diplomatic relations with Communist China, Albania, and Israel. In fact, within weeks of establishing himself in power, Ceausescu showed strong tendencies on Romanian self-sufficiency, especially in regards of procuring armament for his military. Thus, while Romania was receiving substantial military equipment and training from the USSR in the 1950s, since the late 1960s it began resisting Soviet efforts to renew and reinforce the assistance: correspondingly, Romanian Army, Navy and Air Force were soon free of Soviet advisers. Before long, the Romanian dictator was a torn in the side of the Soviets. In August 1968, when the USSR and all other countries of the Warsaw Pact invaded Czechoslovakia, Ceausescu denounced the invasion in a public speech, declaring it for a brutal interference in a sovereign country. Romania was the only Warsaw Pact country not to participate, and subsequently it remained only half-hearted member of the Eastern Bloc. On the contrary, in the following year the Romanian dictator established an increasingly good image of himself in the West, which was mostly due to his stand against the Soviets, and his good relations with France (resulting in contracts for licence production of Pumas and Alouette helicopters, as well as Renault cars), United Kingdom (resulting in contracts for licence production of Rolls Royce Viper engines, BAC 1-11 and BN-2 Islander aircraft), Canada (resulting with the first non-Soviet nuclear reactor built in Eastern Europe), USA (with particularly good relations with Nixon’s administrations) were rising eyebrows in Kremlin time and again. However, Ceausescu ruled Romania with help of the “Securitatea” – the State Security Agency, which was foremost busy controlling all aspects of public life in Romania through intelligence and repression. Securitatea was involved in espionage of literally everybody: like the former “Stazi” in East Germany, it maintained a wide net of informants, infiltrating economic structures, financial institutions, the executive and the legislature. The Romanian state security was maintaining a huge net of listening devices used for intercepting phone calls, supported by a powerful computer-controlled system of Western origin. In this way, the agency was omni-present in every bureau, shop or home around the country. While this system was mainly unknown in the public, to those in know Ceausescu explained that it was foremost tasked with controlling the loyalty of workers and military to the Communist party, as well as ascertaining that everybody is at his work when this was needed. In fact, of course, the Securitatea’s eavesdropping system was not only used for keeping everybody under control, but also for strategic propaganda: with the help of information obtained in this way, the authorities were able to find dissidents, to steer the public opinion in interest of the regime, and exercise pressure upon – or outright blackmail – politicians, judges, military and police officers. In the 1980s, the Romanian regime became increasingly radical and isolated, with a very strong nationalist character. Like Ceausescu, the Securitatea was hated in the public, but nobody was able to admit this openly, then the omni-presence of informants and agents ascertained that any dissident could be swiftly and decisively dealt with. At the political level, the Romanian regime saw the “Perestroika” efforts of the Soviet Leader, Gorbachev, almost as another Soviet intervention in Czechoslovakia: Gorbachev’s drive to replace old Communist leaders of East European countries by reformers was considered dangerous. Not without a reason, then most of the new leaders in post-Communist Eastern Europe almost immediately sided with the West. By 1989, Romania was the last of the Warsaw Pact countries in which there were no reforms. The reformist Soviet leadership was not interested in having a potentially hostile regime on its borders: it could, however, not support an opposition or a reformative wing within the Romanian Communist party as there was none. Besides, the Securitatea would quite certainly learn about such efforts. But, if there was a popular uprising, and a military repression, the Soviets would be provided with a reason to launch an invasion with the reasoning of “protecting Romanian people from their own dictator”. Except in their politics, Romanians showed strong self-sufficiency tendencies in procuring armament for their military. While receiving substantial military equipment and training from the USSR in the 1950s, since the late 1960s they began resisting Soviet efforts to renew and reinforce this assistance: Romanian Army and Air Force were free of Soviet advisers. Romania has an old and proud aviation history, being one of the first countries where aircraft were imagined, built and flown, as well as a rich history of domestic aerospace industry. The first military air unit of the Romanian Army was established already in 1893, and was a balloon observation unit. As early as 1903, the first plans for an original aircraft were published, but it was not before 1906 that this plane was indeed flown by its inventor, Traian Vuia. Nevertheless, already four years later the first fan-jet powered plane in the world was built and flown – even if in an uncontrollable fashion – by Henri Coanda. Romania became only the fifth nation world-wide to have an air force established as a separate military branch: the Romanian Flying Corps came into being already on 10 August 1915, as a branch subordinated directly to the Ministry of War, and having 80 pilots and 25 air observers at the time. During the World War I, this corps actively participated in fighting against Austro-Hungarian and German forces, before the country was overrun by these. The new air arm was established in 1918, and experienced its “Golden Ages” in the 1920s and 1930s, when it was mainly equipped with domestic airplanes manufactured by no less but seven Romanian factories. Over 2.000 military and civilian airplanes were built by Romanian companies within 18 years. In 1940, a number of German instructors arrived and the Royal Romanian Air Force was completely reorganized and then significantly increased, so that it participated very actively in the war against USSR, between 1941 and 1944. By the early 1944, however, the Air Force was severely depleted and weakened due to increasing number of Allied attacks against strategically important oilfields in Ploiesti area. On 20 August 1944, the Red Army breached the Romanian front in Moldova, and three days later a coup led by King Michael deposed the military dictator Antonescu and his cabinet, leading to fierce fighting between the Romanians and Germans, on 24 and 25 August, involving both air forces. When the Soviets finally reached Bucharest, on 30 August, the south of the country was already free of all German troops: the rest of these retreated behind Transylvanian mountains. Thus, the Romanians changed side on their own, right before being overrun by the Soviets. Afterwards, the Romanian Air Force actively fought against Germany during campaigns on Romanian, Hungarian, Czechoslovak and Austrian territories. In 1946, the prefix “Royal” was dropped and the Air Force – “Fortele Aeriene ale Republicii Populare Romane” in Romanian language – was reorganized along Soviet lines. The first Yakovlev Yak-18 fighter jets were supplied in 1950, followed by Yak-23s and MiG-15s, three years later, and MiG-17s in 1955, when the official designation of the air force was changed to Aviatia Militara (Military Aviation – AM). In 1958, the first supersonic fighter – MiG-19 – entered service, followed by MiG-21F-13s, just three years later. At the same time also the first helicopter units were established, flying Soviet-made Mil Mi-2s and Mi-4s. In the 1960s and 1970s, Romania re-established its military aviation industry and obtained licence for production of some Western types, including Aérospatiale SA.316B Alouette III and SA.330 H/L Pumas. Simultaneously, a strike fighter was developed and manufactured in cooperation with Yugoslavia, in the frame of the JUROM project, that resulted in the IAR-93/J-22 Orao – the only non-Soviet fighter-bomber ever built and flown in an air force of a (at least officially) Warsaw Pact member state. As of 1989, the AM had approximately 32.000 personnel, of which less than one third were conscripts. The air force operated 512 combat aircraft, and was responsible for transport, reconnaissance, helicopters and the national air defence system, with the primary mission of protecting and supporting the ground forces and defending the country against invasion. Divided into three tactical divisions, each of which had two regiments of two or three squadrons of interceptors and one of ground-attack aircraft, the AM mainly flew Soviet-made MiG-21s and MiG-23s, but the first MiG-29s were available as well as a large number of IAR-93s. Finally, in December 1989, just a few days before the revolution against Communism began, the first 4 MiG-29s arrived in Romania. Ianca AB 49 Fighter-Bomber Regiment - 1/49 Squadron IAR-93 - 2/49 Squadron MiG-15/S-102 Boboc AB (School of the AM) 54 School Fighter-Bomber Regiment - one squadron of L-29 - two squadrons of L-39 ZA Mihail Kogalniceanu (Black Sea) 57 Fighter Regiment - 1/57 Squadron, MiG-29A/29UB (not operational) - 2/57 Squadron, conversion to MiG-29 - 2/57 Squadron, MiG-23MF/23UB - 3/57 Squadron, MiG-21MF/21UM Turnisor AB (Sibiu) 58 Helicopter Regiment - 1/58 Helicopter Squadron, IAR-316 - 2/58 Helicopter Squadron, IAR-330 Ghimbav Airfield/ICA Brasov (Brasov) 58 Helicopter Regiment (det.) - 1/58 Helicopter Squadron, IAR-316 Tuzla AB 59 Helicopter Regiment - 1/59 Helicopter Squadron, IAR-316, IAR-330 Titu AB (north-west of Bucharest, also known as Boteni) 61 Helicopter Regiment - 1/61 Helicopter Squadron, IAR-316, IAR-330 Tecuci AB 60 Helicopter Regiment - 1/60 Helicopter Squadron, IAR-316 Craiova AB 67 Fighter-Bomber Regiment - 1/67 Fighter-Bomber Squadron, IAR-93 - 2/67 Fighter-Bomber Squadron, IAR-93 Luna AB (Campia Turzii) 71 Fighter Regiment - 1/71 Squadron, MiG-21MF/UM - 2/71 Squadron, MiG-21M/UM Caransebes AB 73 Helicopter Regiment - 1/73 Helicopter Squadron, IAR-316, IAR-330L Borcea AB (Fetesti) 86 Fighter Regiment - 1/86 Squadron, MiG-21 MF/UM - 2/86 Squadron, MiG-21 PFM/US - 38 Reconaissance Squadron, Harbin H-5B, HJ-5 Otopeni AB (Bucharest) 90 Transport Regiment An-2, 24, 26, 30 Deveselu AB 91 Fighter Regiment - 1/91 Squadron MiG-21 MF/UM - 2/91 Squadron MiG-21 PFM/US Alexeni AB (east of Bucharest) 94 Helicopter Regiment - 1/94 Helicopter Squadron, Mi-8T - 2/94 Helicopter Squadron, Mi-8T Giarmata AB (Timisoara) 93 Fighter Regiment - 1/93 Squadron, MiG-23 MF/UB - 2/93 Squadron, MiG-21 MF/UM - 31 Reconnaissance Squadron MiG-21R Bacau AB 95 Fighter Regiment - 1/95 Squadron MiG-21 PF/U - 2/95 Squadron MiG-21 PF/U Someseni airport (Cluj) - 132 Helicopter Squadron, IAR-316B In addition to aircraft, as of 1989, the Romanian air defences have had around 3.000 SA-2, SA-3, SA-6, SA-7, SA-8 and SA-9 missiles. Most of SA-7s and SA-9s were operated by the army, as were some SA-6s and SA-8s, together with a large number of quadruple 14.5 mm machine guns (ZPU-4), and heavier 57 mm (S-60) and 85 mm anti-aircraft guns.

The revolt of Romanian masses against the oppressive regime of Ceausescu and Securitatea began in the town of Timisoara, on 15 December 1989, when ethnic Hungarian reverend Laszlo Tokes held a speech in front of a group of his followers. What started as a small meeting turned into a major demonstration against Ceausescu’s regime: riot police, together with a significant contingent of the omni-present Securitatea and Army troops under command of Gen. Victor Stanculescu (later Minister of Defence) attempted to disperse the crowd of several thousands, causing a noisy and bloody battle in the streets. Timisoara was quiet the next day, and it appeared as if the regime was in control of the situation, but on 17 December a huge crowd gathered again, marching on the Communist Headquarters at city hall. Once again, the security authorities reacted with brutality: tear gas and water cannons were used initially, but then the security forces – unclear if Army, Police or Securitatea agents – opened fire into the crowd, killing dozens. This time the fighting continued into the next day, as the Executive Political Committee in Bucharest (Ceausescu was, by accident, on a state visit to Iran) ordered the military and police to neutralize any resistance. Immediately upon returning from Iran (where, between others, he negotiated a possible sale of over 100 IAR-93 fighter-bombers to the IRIAF), Ceausescu met his closest associates. There are differing versions what happened as next: according to some, the dictator agreed to resign, but was dissuaded from doing so by several of his cronies. According to others, he proclaimed martial law, blaming the uprising on “Hungarian Fascists”, and ordered troops to open fire on demonstrators. When, on 20 December, some 50.000 people demonstrated on the streets of Timisoara, however, most of the Army troops sided with them.

Taken by surprise by the force of revolt, Ceausescu attempted to buy time. He sent negotiators to Timisoara while deploying additional troops to crush the rebellion; simultaneously, on the evening of 20 December, he appeared on the TV, explaining that the unrest in Timisoara was a deed of “hooligans”. Ceausescu’s TV-appearance was closely monitored by the AM personnel based at Giarmata AB, near Timisoara. The situation there was very tense already since 16 December, when the locally-based 93 Fighter Regiment was put on alert. Contrary to the rest of Romanian population and members of armed forces, the officers of the 93 Regiment knew exactly what was going on because they were in telephone contact with their families in the city. An AM pilot of this unit later recalled in an interview to Razvan Belciuganu (published by Jurnalul National, on 20 September 2004) about what happened on the evening of 20 December: - “…the pilots decided they had to do something. The only ones who believed what Ceausescu said were the unit commander and the counter-intelligence officer. They were both escorted out of the air base at gunpoint. The commander of the air defence unit at the base told the pilots he had orders to shot down any airplane attempting to take off. - “Will you shot?” asked the pilots. - “It’s an order!” he replied. - “The one who gave you that order is no longer at the base. So we’ll come to an agreement when the time comes. Meanwhile prepare to defend the airfield if we are attacked from the air!” said the pilots. The pilots decided that if there was any sign that the base would come under attack from other units of the Romanian armed forces, they would take off and seek refuge in Yugoslavia – fighting their way out if it was needed. All the MiG-21s and MiG-23s in operational condition were armed with air-to-air missiles and refuelled. The commander of the 1/93 Squadron, Colonel Surcu, demanded “large air-to-ground, radio-guided missiles” to be mounted on his aircraft (almost certainly Kh-23 air-to-ground missiles): if they were to flee to Yugoslavia, he was determined to strike the headquarters of the Securitatea in downtown Timisoara on the way out. Simultaneously, three trucks loaded with machine guns and ammunition were prepared for evacuation of ground personnel: in the case of an attack against the airfield, they were to set the fuel and ammunition storage buildings on fire and fight their way out or set for Yugoslavia on secondary roads. By the morning of 21 December, problems for Ceausescu’s regime were brewing at the ICA Brasov facility, in Ghimbav, near Brasov, a factory that was manufacturing and overhauling licence-built Aérospatiale SA.316B Alouette III (as IAR-316s) and SA.330H/L Pumas (as IAR-330s). There, the few IAR-316 Alouettes from 58 Helicopter Regiment in operational condition were ordered to be prepared and armed for an attack against Timisoara. Each helicopter was armed with four launchers for four unguided rockets calibre 57mm. The pilots of this detachment were not the least pleased with the idea: they went through assembling facilities, explaining to the assembled workers about their orders, and expressing their discontent. The news spread rapidly, and within minutes, larger groups of workers gathered at the apron of the local airfield. ICA Brasov’s director, Major Ioan Georgescu, appeared as well, and was immediately faced with questions why was the truth about Timisoara hidden, as well as demands for the helicopters not to be sent there. Colonel Arama, the test pilot at ICA Brasov, took off in an armed IAR-316 and took a position some 30m above the crowd. Noticing this, the workers bursted in rage, screaming at Georgescu and others: - “Is this why we are building helicopters? So you can kill us with them? Make it land immediately!” Under pressure, Georgescu ordered Arama to land at once; instead, the pilot flew some 10km away, towards Sanpetru, where he fired his unguided rockets into an empty forest. On return, Arama landed near the crowd, where his helicopter was immediately checked. Finding that its rocket launchers were empty, the engineers took the pods and batteries away from this and all the other operational helicopters, and decided to keep them under guard in order to prevent any kind of retaliation. The rest of workers then marched to Brasov, where they joined the people already demonstrating in the streets.

Obviously without information about first unrests within the military, Ceausescu was determined to keep himself in power. On the freezingly cold morning of 21 December, he appeared in Bucharest to address a crowd of several tens of thousands in a televised speech. All of a sudden, calls from the crowd began to interrupt his speech; Securitatea agents reacted by beating and arresting some of the protesters. Then the situation went out of the control, when the mass became violent and attempted to break police cordons. Security forces opened fire, killing (at least) 13, and arresting dozens of civilians. The fighting spread and chaos ensued as the crowd refused to disperse. The chaos that followed Ceausescu’s last public appearance was the signal that his power was crumbling. Even more demonstrators assembled in Bucharest and other large Romanian cities on the morning of 22 December, huge crowds locking in standoffs with the Army at all the main squares. The situation became even more tense when news began to circulate that there was dissidence within the military. Indeed, in the night to 22 December, the popular uprising was exploited by a group of former high-ranking Party officials and military officers to seize power. Some of the men within this clique had been plotting a coup against Ceausescu already since the 1970s. After securing the backing of a larger number of senior Securitatea-officers and units, on 22 December they announced on the national TV to have taken control of the government. The backgrounds of this coup remain unclear to this day, and there are not few Romanians all too concerned to talk openly about what exactly happened. It appears, that the coup was supported by the Soviet intelligence, foremost the KGB and GRU, which at least used to have contacts with the former Romanian Minister of Defence, General Nicolae Militaru. If nothing else, Militaru at least gathered around himself a group of more influential military men than his rivals in the Securitatea, led by Virgil Magureanu could. Sensing the danger from within the circles of what should have been his supporters, Ceausescu was forced to leave amid scenes of troops siding with protesters. He has left the Central Committee Building around noon of 22 December, on board a Dauphin helicopter, which was so overloaded that the pilot struggled to get it airborne as some demonstrators reached the roof. Although his remaining followers suggested him to fly to Otopeni AB and then leave for Iran or North Korea, he stubbornly refused, ordering the pilot to fly to Poliesti or Pitesti, with intention of rally the local workers around himself and regaining power. Once Ceausescu was away, all armed forces units in the streets of Bucharest sided with the crows. From the moment the clandestine activity of various groups within the Romanian military and security apparatus began, the country was subjected to an act of unprecedented electronic warfare. Jamming of radars and radio communications was widespread; vivid operations of unidentified helicopters, aircraft and even unmanned vehicles was recorded as flights were observed penetrating Romanian airspace from various directions, and Romanian fighters and helicopters were scrambled to intercept. For strong political reasons – mainly connected to the wish of new Romanian authorities to keep the image of the military “clean” of any actions against populations, but for other reasons as well – most of this clandestine activities remain unexplained until today, even if there are strong reasons to suspect not only a massive involvement of the Securitatea, but also that the Soviets were closely monitoring the developments in Romania, perhaps with the objective of preparing an armed intervention of one sort and purpose or the other. The effects of these operations, as well as the omni-presence of the Securitatea, were amplified by the tension and confusion within the military, resulting in a number of friendly fire incidents, foremost between Army units. The first signs of unusual aerial activity over Romania were recorded around 18:30hrs, on 22 December, immediately after the landing of a BAC 1-11 transport aircraft at Arad underway on the line Bucharest-Timisoara-Arad-Bucharest, carrying Generals Nuta and Mihalea with their staff. Most of AM radars around the country have detected numerous unidentified contacts. The preliminary report published by the Romanian Secret Service about events in Timisoara, in December 1989, cited that the locally based UM 01942 (“Military Unit 01942”, a radar unit of the Timisoara Air Defence Division of the Romanian Air Force), had its radar stations at maximum alert, and that these detected a large number of objects moving towards the state border from north, north-west, west and south – from the USSR, Hungary, Yugoslavia and Bulgaria at the same time. At the time, there was no jamming yet, and thus the Romanian operators considered these targets to be real. Approximately 20-25km away from the border, all the targets disappeared from the radar screens – only to re-appear one hour later, this time well inside the country, and apparently converging on various AM air bases and air defence sites. Officers of the UM 01942 have had no doubts: they were tracking a total of 41 unidentified, slow moving objects inside the Romanian airspace, all flying at very low levels, and this meant that an aerial attack against their country was underway. Major Stelian Bouleanu from 93 Fighter Regiment later recalled: - “…at 19:00hrs, I got orders to take off. The plane was armed with air-to-air missiles and live rounds for the gun. A number of targets appeared on radars and my mission was to find and destroy them – if ordered to do so. I went somewhere about the Mures River, and patrolled approximately between Lipova and Savarsin… No helicopters! - The radar (GCI) then gave me other coordinates and I flew to Caransebes. Nothing! Lugoj…Nothing! I’m flying around the west of the country, looking for invisible helicopters, and can’t find anything. After this I came to a very clear conclusion: no airborne force was attacking us. Our radars went crazy, inventing whole groups of helicopters that appeared to be approaching, landing, bombing or attacking urban areas and economic objectives! I reported about this when I returned to my airfield. The UM 01864/C, at Pecica, detected a helicopter. Shortly after, a helicopter was observed while landing troops at Semlac. Two others appeared seconds later: one in Pecica and another in Curtici, while two helicopters were detected while approaching Arad airport. Local air defence units immediately opened fire. Radars of the 1st Missile Brigade, composed of nine battalions spread at a distance of 30 to 40 kilometres around Bucharest, and responsible for the defence of Romanian capital, also detected a number of targets. One of its officers later recollected: - The general situation in the air offered the image of an air attack against the capital and heliborne landings. This picture appeared on the main radar scopes of the brigade, but also on local radars of other air defence units around Bucharest. Simultaneously, there was information that these sites were also attacked from the ground. It looked like the enemy planes came from the Danube, manoeuvring towards Bucharest, or coming directly from the Sea, above Constanta and Urziceni. Our missile units appeared subjected to a total war! In addition to the 1st Missile Brigade, the 1st Romanian Army has had a SA-6 regiment near Bucharest as well, with one battery on permanent quick alert. Additional air defence units were deployed at Otopeni and Baneasa airports, as well as with the 57 Tank Division at Pantelimon, which has had one battery in full alert at any given time. During the night, the situation became more and more complex, with additional targets emerging. Eventually, ever more units were granted permission to open fire. The Commander of the 1 Missile Brigade, a highly experienced officer with ten live firing exercises on ranges in Kazakhstan, as well as an extensive briefing on experiences from the Lebanon War, in 1982, ordered firing action only against targets that were clearly within the kill zone. His unit fired six SAMs, all of which appeared to have hit. Afterwards, suspecting a bluff, he ordered the SAMs to cease fire and sent his subordinates to bring him at least once piece of metal from one of downed aircraft. The commander of the battery positioned near the village of Miahai Bravu, reported that some of the engaged targets should have been hit only six kilometres from his position. He sent a team there, but this found nothing. While the SAMs ceased fire, anti-aircraft guns continued firing. For the rest of the night additional reports about activity of unidentified flying objects inside the Romanian airspace were reported by other AM units as well. Around 22:24hrs, an unidentified helicopter was detected in south-eastern Romania. Coming from Otopeni, it approached to a point some 40km west of Alexeni AB. When only eight kilometres away, around 22:38hrs, it disappeared from the radar, only to re-appear two minutes later, now barely four kilometres away. At a distance of two kilometres, it suddenly made a 90 degrees turn to the left, then reached the Ialomita River, where it turned again at 90 degrees, following the river towards west. Several of people at the air base had the opportunity to take a look at this helicopter when it passed by and identified it as a French-made Aérospatiale (later Eurocopter) SA.365 Dauphin: there were four Dauphins in Romania at the time, all used for VIP-transport. Almost simultaneously, a similar scene occurred at the Titu AB, the main base of the 61 Helicopter Regiment, and only few kilometres north-west from Otopeni. What appeared to be a big transport aircraft was detected some 40km due west, at an altitude of only 200m and speed of about 400km/h. This plane was underway towards Alexeni, and definitely larger than any of the Antonov An-24, An-26 or An-30s in AM service at the time. By 22:38hrs, the plane was apparently trying to land in Alexeni, when it disappeared from the radar, some 15km away from the runway. Around 22:44hrs, an aircraft was indeed observed approaching Alexeni AB, simultaneously with a helicopter (probably again the same Dauphin observed previously). One minute later, anti-aircraft guns of this airfield opened fire at both targets (which were underway with their navigation lights turned off), but these climbed to a level of between 3.000 and 4.000m, evading fire. After climbing, the aircraft continued towards east, reappearing on radar at 22:47hrs, now some 15km east of Alexeni, at a level of 4.000m and speed of 600km/h. As Major Bouleanu concluded already in the early evening, no aerial attack against Romania occurred. Most of the dozens of targets detected by the radars of the UM 01942 were fake – a result of powerful jamming from unknown sources. With very few exceptions, none of the targets could be tracked for periods of time that would be sufficient to mount an interception. One of staff officers from the 1 Missile Brigade concluded, - “This action could have been undertaken by only one “actor”: the Soviet Army. Before 1989, all our battle positions and their geographical locations were reported to Moscow – in accordance with the Warsaw Pact Treaty. The Soviets also knew all our communication-, range-finding- and guidance frequencies – current and reserve ones. This was confirmed by Commander Radu Borcea, head of the EW-Section of the AM: - “Most of our equipment was Soviet-made. They knew what they gave us, they knew the frequencies, they knew everything. This is how all the interferences in our communication frequencies can be explained.” Correspondingly, the Commander of Romanian Armed Forces, General Gusa, made a fateful decision, ordering the AM interceptors and helicopters to remain on the ground, and air defence units to open fire at anything that was flying. In the wake of this order, clandestine activities inside the Romanian airspace increased. Subsequent inquiry by the AAT division of the Romanian military concluded that the involved forces – especially those that initiated electronic warfare attacks against AM radar net – did not belong to any of Romanian military or security branches. This conclusion is clearly recorded in the Document S443/02-04-1990, issued by the Central Institute for Military Equipment: Technical characteristics of the assets existent in the Romanian armed forces exclude the possibility of conducting such actions by the forces destined for electronic warfare available within the country. Not all of the attacks were fake: in fact, some of electronic warfare actions have obviously been coordinated with ground attacks. These were not particularly fierce, and mainly resulted in exchanges of small arms fire, but this was well placed. At 00:35hrs of 23 December 1989, Titu AB was attacked by small arms fire. The guards returned fire and the attackers disappeared. Almost simultaneously, targets resembling helicopters were detected while approaching Giarmata AB, but they disappeared from radar scopes. In the following hours and by the early morning, the AM radar at Boboc AB, north of Alexeni, detected the following targets during this night: - two or three objects underway south of Ramnicu-Sarat, flying towards Braila at various altitudes and speeds; - Between six and eight objects in the area of Bucharest, flying towards Ploesti-Mizil, at altitudes between 500 and 5.000m - Between six and eight objects flying from Lipia to Boboc at speeds between 150 and 300km/h. At 01:15, 01:40, 02:20, 02:24, 04:01 and 05:45hrs, a total of six drones were observed while approaching Alexeni AB. Each of them operated as a single-ship that carried a large red light at the rear. All flew at a level around 500 metres, at speeds between 100 and 150km/h. Most of these helicopters approached from the direction of the village Manasia, nearby. All were fired upon and every time they would make 120 degrees turn to the left or right, exploding some five or ten seconds after changing direction. No wreckage was found on the following morning. Elsewhere, AM air defence units fired a number of heavy SAMs. An SA-6-site near Circea, defending Craiova AB, near the border to Yugoslavia, reported shooting down three helicopters between 01:40 and 02:55hrs. The search teams found no wreckage on the ground. During the same period of time, the personnel of the 1/83 Helicopter Squadron at Tecuci AB – in eastern Romania - reportedly observed two helicopters passing by and opened fire at them, while at Tuzla AB (on the coast of the Black Sea), personnel of the 59 Helicopter Squadron observed helicopters approaching the airfield and turning off their navigation lights. Given that radio intercepts showed that their crews were communicating in Romanian, they were not shot at. At 01:55hrs, somebody dropped parachute flares over Giarmata AB. The personnel of the Boboc AB, the base of the AM Flying School, received orders to send two trucks to a nearby ammunition depot and pick up some bombs to arm their aircraft. Strange enough, at the same time the command post received a message that two trucks with terrorists dressed in blue overalls are moving in direction of the ammunition depot. Then, as now, blue was the colour of overalls worn by AM ground crews, but the Commander of this airfield failed to notice this and immediately scrambled two L-39ZAs, with orders for the trucks to be destroyed. To the luck of ground crews in trucks, the ammunition depot was situated in a dense forest, and the L-39-pilots could not locate the trucks by darkness.

While Giarmata AB was one of main areas of activity in the night from 22nd to 23rd December, 1989, most of action – and most of fighting – was reported from the Mihail Kogalniceanu AB, on the Black Sea coast. The first sign of trouble were four helicopters that approached at high altitude (between 4.000 and 6.000m), at 02:02hrs, identified by their navigation lights. When air defences opened fire, all four disappeared. Slightly over half an hour later, this air base was attacked by small arms fire: the perimeter was breached and the attackers fired at installations belonging to the 57 Fighter Regiment. After some time, the defence forces managed to repel this raid. Already around 04:40hrs, a single helicopter was spotted between six and eight kilometres away from the runway and approaching. Once again, as soon as air defences opened fire the helicopter disappeared. Later on it was reported that sometimes during this night, an IAR-330 Puma helicopter (No.76) of the 59 Helicopter Regiment from Tuzla AB, landed in damaged condition at Kogalniceanu AB. The crew was safe, but it remains unclear why this helicopter took off in the first place, given the general order for all flying assets to remain on the ground. Equally, it remains unclear if this helicopter was damaged by fire from local air defences, or in another incident. By the morning of 23 December, news appeared that there was fierce fighting on the streets of several Romanian cities. Confusing reports about brutality of the security authorities, Army units switching to the side of people and battling security forces, and Ion Iliescu emerging as a leader of the National Front that made a list of demands on the government arrived, increasing confusion. Around 12:50hrs, unknown helicopters and ground forces were reported 27km away from Sfantu Gheorghe, in the Danube Delta, and two MiGs were scrambled from Kogalniceanu AB to inspect. Whether these were MiG-23s or MiG-21s remains unknown (MiG-29s were not operational yet), but reports in the Romanian press indicate they did two attack passes, launching unguided rockets (probably calibre 57mm, from UB-16 or UB-32s), and larger rockets (perhaps S-24s) as well. After the second pass, their pilots were ordered to abort the attack and return to base. Shortly after, a second pair of MiGs was ordered to perform a combat air patrol in the area of Sulina, Macin and Babadag, but they found no targets or any other unusual activity. Additional missions were flown by MiGs from Kogalniceanu in the afternoon. Between 15:25 and 16:25hrs, several reconnaissance sorties were flown along the coastline and off-shore oil rigs, as well as over Sfantu Gheorghe, but no unusual activity was detected. Finally, between 18:45 and 19:26hrs, a flying object was tracked over the Black Sea, some 25km away form the coast. No lock-on by the local SAM-units could be obtained however, as heavy active jamming was emitted by the target. Except for MiGs from Kogalniceanu AB, other flying units of the AM were active on this day as well – despite of the order from Gen. Gusa. The Alouette helicopters at ICA Brasov were returned to flying condition and armed already during the 22nd December, and they flew several combat sorties in support of the uprising, opening fire on a number of occasions. Several found themselves on receiving end: one Alouette landed in Brasov with minor damage during the night from 22 to 23 December, while another returned with a bullet in one of the pilots’ seats. Also, sometimes during the 23rd, an unknown helicopter opened fire against an Army armoured personnel carrier near Otopeni AB, killing one soldier and causing the vehicle to catch fire. During the same day a Puma (probably from Titu AB) was ordered to attack some “terrorists” supposedly hiding in a cemetery in Bucharest. The Puma crew found some activity going on and opened fire with a machine gun mounted in the door. The suspects were in fact some guys digging a grave: luckily none of them were hit. The whole incident was filmed by a TV crew which was passing trough the area.

The next crisis developed in the west of the Romania, announcing the night of most numerous bogus radar contacts, unidentified aircraft and helicopters, skirmishes and other kinds of incidents during the whole crisis. Once again, a number of “attackers” appeared on radar scopes: “helicopter”-type targets were approaching from Sannicolau-Timis towards Arad, while others were operational over the Ceala forest. UM 01380 confirmed detection of helicopters even over downtown Arad, and the air defences of the local airfield opened fire again – without any success. Shortly after, two unknown aircraft were spotted over the city, while a formation of helicopters was detected while approaching from Caransebes (base of the 73 Helicopter Regiment). Two helicopters were observed while passing the valley of the Mures River and landing near the chemical plant at Vladimirescu. The chaos was complete. By the morning of 24th December, various AM units were to report detecting a total of no less but 365 unidentified flying objects with their radars, of which a “formation” of 14 flew an “attack” against UM 01942. Between 16:20 and 23:20hrs, several aircraft were detected approaching Deveselu AB at ranges between 12 and 30 kilometres. When the anti-aircraft defences opened up all targets turned away and climbed, exiting the range of the guns. This air base remained under similar “attack” from 00:55 until 16:55hrs of 24 December. At 01:30hrs on 24 December, a helicopter was spotted some four kilometres away from Fetesti/Borcea AB. Moments later, it opened fire against housing facilities before turning away towards west and apparently landing some eight kilometres away. Search teams found nothing at the supposed landing site. Half an hour later, another MiG was scrambled from Kogalniceanu AB, this time to intercept a target approaching to 40km from north-east. As soon as the MiG was airborne, the target turned away, flying along the Danube river. This time, the AM interceptor was well placed, and the pilot managed to establish a lock-on. Before he could fire, however, the target began emitting strong active jamming, and it disappeared from the radars around 02:56 hrs. Obviously in response to this action, Kogalniceanu AB was again attacked by unknown ground forces, around 03:30hrs, approaching from north-east. After a short fire-exchange these retreated in the same direction from which they came. Obviously, whoever was interested in steering unrest and insecurity at this airfield was not particularly successful. By the morning, there were larger and smaller battles raging between various Army units, supported by civilians, and unknown elements all around the country, and especially in Bucharest. During the fighting in the suburbs of Romanian capital, an IAR-316B Alouette III was shot down by small arms fire, near the road leading to Craiova. The pilot has got a bullet in the butt, but survived, together with the rest of the crew. With Ceausescu captured, put on a short trial and shot (together with his wife), the National Front claimed control of the revolution and established a provisional government. Uncertainty and terror still prevailed however, as different elements of the regime fought for their survival – openly or clandestinely. Around 07:00hrs in the morning, the IAR-330 Puma “72” of the 58 Helicopter Regiment from Sibiu was declared as missing. Its wreckage was found later in the day, near Alba-Iulia, in central Romania, together with remnants of the dead crew and passengers – generals Nuta and Mihalea. The cause of this crash remains unknown until today, but some sources claimed that it was shot down by SA-7 MANPADs (it is interesting to note, that later on a small monument was established on the crash site, but mentioning only the three crewmembers of this helicopter). During the day, the AM lost two other Pumas, while one was damaged. Two Pumas from 61 Helicopter Regiment came under fire from air defence troops shortly after taking off from Titu AB. One of the helicopters transported ammunition: like in a miracle, the crew managed to land it safely and run away before the helicopter blew up. The wreck burned for two hours, with exploding ammunition popping out from time to time. The second IAR-330 from this formation was hit as well, but suffered only minor damage. The second loss was one of the most painful of the whole crisis. It occurred around 18:35hrs, when the helicopter with side-number “89” was sent from Tuzla AB to look for two unidentified “helicopters”, tracked by the radar. In turn, the Puma was intercepted by an 86 Fighter Regiment MiG-21MF; after the GCI told the pilot that everything that is airborne is “enemy”, he opened fire downing the helicopter and killing all four on board. The wreckage of the unlucky 89 came down between villages of Ion Corvin and Adamclisi. Finally, at Alexeni AB, two Mi-8Ts of the 94 Helicopter Regiment were fired at and hit several times some five minutes after take off by the elements of an air defence unit at Adancata. This obvious case of fratricide fire illustrates at best the chaos caused by sabotage within the chain of command of the Romanian military in these days. The air defence unit in Adancata was subordinated to Alexeni AB, and its commander was in the central command post at Alexeni when the incident occurred. He and his subordinates were advised that two friendly helicopters would pass overhead, but immediately afterwards the personnel at the anti-aircraft battery received a call from someone claiming to be a well-known high ranking officer, who advised them to shot down the helicopters. The crews of two Mi-8s were lucky, then nobody got hurt. The same kind of diversion led to the downing of the two Pumas at Titu AB mentioned above.

In the early hours of 25 December, search parties from Mihail Kogalniceanu AB found signs that unknown troops were present in the field some five kilometres south-west from the airfield for some time. Nothing special was found, except remnants of few cigarettes, unimportant pieces of military equipment and few shallow shelters, but it was assumed that the ones who attacked the airfield on the previous two nights camped there. According to unconfirmed rumours, the attackers could have been the Soviet SPETSNAZ troops: why would these undertake such an operation, however, remains unknown. Meanwhile, the Romanian national TV showed the bodies of Ceausescu and his wife, thus marking the “end” of the eleven days long “uprising”. Nevertheless, fighting continued in Bucharest and several other Romanian cities, mainly between various Army units, resulting in even more civilian victims. Most of civilians were killed by 19-years old Army conscripts, majority of whom were drafted barely two months before the uprising, and had only one live fire exercise behind them, but found themselves under immense pressure by officers who ordered them to “fight terrorists” inside the cities. Being “trigger happy”, the young conscripts killed dozens of civilians. The Romanian Army, trained to fight the “World War III”, proved poorly prepared for the situation and the vast majority of engagements were actually cases of fratricide fire – even those that included fully-blown armoured battles – caused by fake orders or diversions: unknown persons would fire at one unit from the general direction of another one and then fled before all hell broke loose. In the days following the uprising, the new Romanian leader, Iliescu, did everything possible to deny that the Army fired on demonstrators – regardless if in Timisoara or in Bucharest: having a vested interest to clean up the military’s image, Iliescu and his aides claimed that Securitatea units and unknown “terrorists” (including Soviets and Arabs) did all the shooting at civilians. While it is possible that some of Securitatea-agents were operating in the guise of Army units, and there is even strong evidence that some “Arabs” were indeed involved in firings against Army and other security units, it is certain that practically all the branches of the Romanian military were involved in attempts to put down the uprising until the moment when Ceausescu fled, on the 22nd . Amazingly – and in spite of what is usually reported in the West - the Securitatea appears to have been an exception. The Romanian state security knew very well what was going on in the Eastern Europe and knew that Ceausescu’s case was a lost one. Besides, already by 22 December, the armed units of the Securitatea and the police were put under military control and – with most of their men locked up in barracks – had almost no active role in the subsequent fighting. Members of the Securitatea were no fanatics (at least most of them were none): correspondingly, the omni-present Romanian state security could not openly side with any side, the dieing regime, military, or the coup-plotters. Surely, the powers of this organisation were such that not few of its elements survived until today, and are still influential in the Romanian society. And, certainly, it is perfectly possible that a number of agents and cells within military or security authorities became active at one point or the other, or have exploited the situation for subversion and diversion, which would explain the number of fratricide-fire incidents that occurred. However, there is no firm confirmation that the Securitatea as organisation actively participated in attempts to put down the uprising of 1989. On the contrary, there are strong indications that most of the actions undertaken to create chaos within the Romanian military were undertaken by foreign powers. For all these reasons, it is solely the lack of efforts of serious historical research on the part of Romanian authorities (as much as the fact that ex-Securitatea people are not especially keen to talk in the public) which is to blame for the Securitatea being blamed for shooting at civilians. So it happened that the only Securitatea’s armed unit known to have actively participated in the fighting was the USLA – a SWAT-type asset, specialized in anti-terrorist and urban warfare. This unit was decimated in one of fratricide clashes with Army, caused by poor leadership and chaos within the chain of command. When it comes to AM’s performance in these chaotic eleven days, some general statistics was published ever since, which provides an insight into how intensive the air – and especially – electronic warfare was. In total, between 22 and 25 December, the AM interceptors were scrambled 52 times: only in five cases were their pilots able of detecting one or more targets with their radars. Except in one case, no lock-ons were obtained – foremost due to severe jamming. During the same period of time, Romanian air force helicopters flew a total of 26 sorties. Air defence units reported even more activity. Timisoara’s AAT Division alone detected 761 unidentified flying objects in this period of time. A number of these were engaged by air defence forces, which opened fire at no less but 1.194 occasions. 58 SAMs were fired in the night from 22 to 23 December alone, of which the 51 Missile Regiment, based at Craiova, launched 29 SA-6s. Some 60% of missiles were observed as detonating near or on target. UM 01215 Floresti, based near Cluj-Napoca, fired four SA-8s, and at Resita a total of 12 SAMs of various types were expended, along with huge quantities of anti-aircraft ammunition. No confirmed SAM-kills were scored – at least none that were ever officially confirmed as such. Search parties sent to supposed crash sites found (almost) nothing: in few cases, small amounts of debris, ranging in weight form 290 grams to 19 kilograms, consisting of metallic foil, burnt plastic and small mechanisms. There were obviously two types of targets: helium-filled balloons with radar reflectors, consisting of metallic-foil, and some sort of small drones, sometimes carrying lights and/or emitting helicopter-engine noises. The later were relatively seldom observed, then they were mainly operated at night, yet their radar echo, size and flight profiles closely resembled helicopters. The only exception regarding results of SAM-attacks might have occurred on 28 December 1989. On this morning a TAROM (Romanian national carrier) An-24RV “YR-BMJ” (c/n 77310801) took off from Otopeni for a flight to Belgrade in what was to be the first international fight since the uprising. Apart from the crew, including pilot Valter Jurcovan, there was only one passenger on board: an English journalist called I. Perry. Perry carried plenty of tapes and videos containing takes of what exactly was going on during the uprising in the Headquarters of the Central Committee of the Romanian Communist Party – one of the hot spots of the revolution. When 55km south-west of Bucharest, the plane was hit by a SAM and crashed into the Malinoasa forest, near the village of Visina. The wreckage was spread over one square kilometre, and all on board – differently reported as between three and seven – perished. Shortly after the crash, a helicopter overflew the area and a number of cars reached the site, the people in the cars collecting the tapes that escaped the crash. The subsequent inquiry found traces of chemical materials identical to those used for propellants and explosives in SAMs: surely, an air defence site belonging to the Titu AB was within the range, but reported no firing that day. The official cause of the catastrophe was subsequently declared to have been either “bad weather”, or “collision with an unknown flying object, that hit the tail area”, while the aircraft was “underway to Belgrade to pick up humanitarian supplies”. It remains unclear how much did the AM – renamed back to Fortele Aeriene Romane following the fall of Ceausescu – draw any important lessons from this event. Certainly, when Romanian military was completely reorganized in the following years, the air force was given priority status and – contrary to air arms of other former Warsaw Pact countries – in the 1990s it was not as drastically decreased in size. On the contrary, while some units were disbanded, and others moved to different air bases, in general, the RoAF was modernized through cooperation with Israel (that resulted in modification of almost all the surviving MiG-21M/MF/UMs in the frame of the Project “Lancer”), and the USA (which supplied four Lockheed C-130B Hercules transports). As usually, no report of this kind could be completed without extensive cooperation of several persons. Sadly, all of our Romanian contributors expressed their wish to remain anonymous. Except for their extensive help with materials and translations, as well as patient explanations, they have also provided translations of most important excertps from the few articles published in Romania, mentioned bellow. While - to our knowledge - there is no complete account of all the RoAF activities during the period between 15 and 25 December 1989, and we consider this one to be the most complete such feature available in the public, we would wellcome any further assitance our readers might be able to provide. Published sources we have used are: - Document S443/02-04-1990, issued by the Central Institute for Military Equipment, Romanian Ministry of Defence, and quoted by the SRI preliminary report about the events at Timisoara - Articles about activities of the RoAF, published by Razvan Belciuganu, in Jurnalul National newspaper, on 20, 21, 22 and 23 September 2004 (mainly based on log books of various RoAF units and recollections of some officers involved). - Account about the downing of TAROM An-24 on 28 December 1989, published in Ziua newspaper, on 17 December 1999. - Article “Radioelectronic and Psychological War against Arad”, by Emil Simandan, published in Adevarul newspaper, and forwarded by Virtual Arad magazine, on 22 December 2005.

© Copyright 2002-3 by ACIG.org |