|

| Search |

|

|

|

|

Central, Eastern, & Southern Africa Database

|

Ethiopia is a country situated in one of the oldest – if not the oldest – area of human habitation: archaeological research in this country has proved that the modern homo sapiens probably evolved there. The original form of the modern-day name of this country was first used by ancient Greeks to refer to the peoples living south of ancient Egypt; modern usage has transferred this name further south, to the land and peoples known until the early 20th Century as “Abyssinia”.

Relatively isolated due to inaccessibility of the high central plateau, Ethiopia experienced introduction of Christianity around the year 330, and a number of attempted Moslem invasions in later centuries. In the medieval ages, three chief provinces came into being: Tigray in the north, Amhara in centre, and Shewa in the south. The seat of the government was usually in Amhara, but at times there have been two or even three kings reigning at the same time. Between 1528 and 1540, Ethiopia was invaded by a Moslem army led by general Ahmad ibn Ibrihim al-Ghazi, and the negus (king) Lebna Dengle Dawit II requested help from Portugal. Despite quarrels between the leaders of the Portuguese contingent that arrived in 1541, and Ethiopian leaders, the Moslems were eventually defeated. The Portuguese were subsequently obliged to make their way out of the country.

Partially because of bitter religious conflicts with the Jesuits, but also due to inner struggles between various rulers, for the following 300 years, the country again remained relatively isolated. It was not before 1855, when Lij Kassa proclaimed himself negus negusti (king of kings) under the name of Theodoros II and launched a campaign to unite the whole country under his rule, that modernisation and opening of Ethiopia began. The rule of ruthless Theodoros came to an abrupt end in 1897, when he committed suicide following a short war with the British, in which Ethiopian army was defeated at Magdala (now known as Amba Mariam).

The Effects of Suez Canal

The end of Theodoros’ rule came at the time the whole area of the Red Sea became strategically important due to the opening of the Suez Canal. The Western imperial powers began battles for the control over the shores: the British occupied Yemen, the French took Obock, Asars and Issa (later known as Djibouti), while Egyptians had the ambition to conquer the source of the Nile and had invaded Sudan.

The Italians were present in the area already since 1870, when Assab, a port near the southern entrance of the Red Sea, had been bought from the local sultan by an Italian company, which, after acquiring more land, was bought out by the Italian government, in 1882. Six years later, the Italians for the first time came into contact with the Ethiopian army. Busy defending their country first against the Egyptians and then against an invasion of dervishes from Sudan, the Ethiopians were not interested in fighting the newcomers. Thus, all the disputes were solved – more or less - through negotiations, the Italians being permitted to keep some 5.000 troops in Eritrea, as their new colony was named.

Finding an agreement with the British, the next Ethiopian Emperor, Yohannis, defeated the dervish invasion, in exchange for Ethiopian part of Sudan that was occupied by the Egypt and free trade of arms and ammunition through the English controlled harbour of Masawa. Yohannis kept his part of the deal, and defeated the Italians in the battle of Matema, in March 1889, but paid with his life. The British broke their part of the deal by handing over the control of Masawa to the Italians.

The new Emperor, Menelik II, had meanwhile done much to unite Ethiopia under his power. One of his early decisions was to, in 1886, move the capital to the Intoto Valley, establishing what later became known as Addis Ababa. Only few years later, the came into a conflict with Italians again. This war culminated in a humiliating Italian defeat during the Battle of Adowa, on 1 March 1896, which resulted in provisional treaty of peace, and Italy recognizing the absolute independence of Ethiopia – which thus became the oldest internationally recognized independent African state – but in exchange for Eritrea.

Thus began the history of the modern-day Ethiopia – the first African country to defeat an European Army. Following the success in the war, Ethiopians invested in modern infrastructure, building the Djibouti-Addis Ababa railroad, post and telephone services. First ministers were appointed, a bank was founded, a hotel and the first hospital opened, followed by first schools.

Emperor Menlik died in December 1913, and was succeeded by his grandson Lej Isayu. Unpopular due to his sympathy for Germans and Turks, as well as support for Moslem minority and his wish to abandon slavery, Isaju ruled only four years, until replaced by his aunt Zauditu and Ras Tafari Mekonen, the son of the hero of the Battle of Adwa, supported by the British, French, and Italian diplomats. With help of Belgian officers and loanded Swiss money, Mekonen established an own army and in a kind of a series of local uprisings established himself in power. In 1930, Ras Tafari Mekonen was crowned as Emperor Haile Selassie.

Italian Revenge

The history of military flying in Ethiopia dates back to 18 August 1929, after the Emperor Selassie was impressed by exploits of Huber Fauntleroy Julian, an African American and the first black person to obtain pilot’s licence in the USA. when a small flying branch of the Ethiopian Army was established at Bishoftu, near Addis Ababa. Initially equipped with six Potez 25A2 biplanes, reinforced by two Junkers W.33Cs, delivered on 5 September of the same year, the Imperial Ethiopian Aviation (IEA) was put under command of a French pilot, Andre Maillet, and mainly tasked with transport- and liaison duties. Maillet was succeeded by another Frenchman, Paul Corriger, in 1930, when the number of available airframes was increased by addition of a Breda Ba.15 and Ba.25 each, a DeHavilland D.H.60 Gipsy Moth, and two Fairman F.192s.

In 1934 and 1935, a number of new aircraft was acquired, including two Beech B17 Staggerwings, two Fokkers (one F.VIIa/3m and an F.XVIII), and a single Meindl AVII. However, there were still only two qualified Ethiopian pilots: Michka Babichef (a son of a White Russian and Ethiopian mother), and Asfaw Ali, while there were no native technicians. Thus, like the rest of the Ethiopian military, the IEA was still underdeveloped and lacked the ability to defend the country when, on the morning of 3 October 1935, Italy invaded Ethiopia from Italian Somaliland.

Only very few reliable records are available from the time about Ethiopian aerial operations. It is certain that the IEA had no combat aircraft or combat-trained national pilots at the time of Italian invasion: although at least one of the Potez 25A2s was still operational and could carry machine-guns, none were mounted. Due to the lack of spares and poor maintenance, only three aircraft were operational on average: all three were unarmed and could thus only be used as light transports. Nevertheless, shortly before and during the war several African Americans were recruited or volunteered to go to Ethiopia to serve as professionals in various fields. The most influential of them was Col. Julian, who was assigned the command of the IEAF in October 1935. Another US-pilot active in Ethiopia at the time was John Robinson, better known as “Black-“ or “Brown Condor”, who completed his pilot’s training and earned his wings from Booker T. Washington’s Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute, in Alabama, in 1920. Invited by the Emperor Selassie himself, Robinson arrived in Ethiopia at the end of May 1935. Operating one of few flyable IEAF aircraft, he participated in the fighting right from the start of the war, transporting troops, ammunition and supplies, as well as the Emperor, from one site to the other. At some point in time, Julian and Robinson have had a public fist-fight, and the former was asked to leave the country. Robinson remained in Ethiopia: although frequently confronted by Italian aircraft and ground fire, and having his aircraft several times riddled by bullets, he was wounded only once.

The third US-pilot in Ethiopia was John H. Spencer, who acted as official military adviser. He is known to have flown some transport- and reconnaissance missions with one of Ethiopian Potez 25s, together with the British Military Attaché, Maj. Holt, as well as Babichef.

Initially, the main IEA’s operational zone was in Dessa area, where the Ethiopian Army field headquarters were positioned. Dessa was several times hit by Italian Air Force, and in one instance even the Emperor had to man an anti-aircraft gun. Eventually, all the efforts of Ethiopian and volunteer pilots were in vain, however: Adowa, the site of Italian defeat from 1896, was captured already on 6 October, and – preceded by a series of air strikes – the Italian troops under command of Gen. Emilio De bono then marched deep into Tigray, where many landlords offered no resistance, while some even sided with the occupiers.

Nevertheless, the rest of the Italian invasion was no “walk-over”: by December, De Bono was replaced by Gen. Pietro Badoglio, because of the slow advance. Emperor Selassie attempted to test the new Italian commander with an attack, but his forces were repelled due to Italian superiority in heavy weapons. The invaders subsequently launched a bitter campaign, supported by air power and artillery bombardments. They also deployed mustard gas, usually sprayed from Italian Air Force aircraft, and not only on the battlefield, but against Ethiopian cities and Red Cross camps and ambulances.

During the war, the Italians deployed their air force mainly for close support and transport purposes. conducted experiments with various types of bombs and projectiles, as well as with dropping ammunition, food and water to ground forces. Most of their planes were obsolete, however, the only modern type being few Savoia-Marchtti bombers. With an opponent as primitive as Ethiopia was at the time, the Italians have got little opportunity to test Douhet’s theory of strategic bombardment, but the town of Harer was fire-bombed, on 29 March 1936. Two days later the Italians won the last major battle of the war, at Maychew. On 5 May, Addis Ababa was captured, and four days later Italians formally annexed Ethiopia (together with Eritrea and Somaliland).

Selassie was forced into exile, first in England and then in Sudan, despite his pleas to the League of Nations for intervention. The fact was that West European powers were not interested in reinforcing the alliance between the Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, and thus Ethiopia was scarified. Robinson survived the fall of Addis Ababa as well, and returned to a delirious welcome back in the USA, announcing the start of a guerrilla war against Italians.

The Italian occupation lasted for only five years, and has had both, positive and negative effects on Ethiopia. On one side, the Italians have done a lot to improve infrastructure, through building roads and bridges, and expanding most of larger cities. On the other side, continuous revolts were crushed by massacres and segregation and the Italian fascists murdered most of Ethiopian intellectuals, resulting in armed resistance, which was to form the basis for the British victory in Ethiopia, in 1941.

The WWII campaign in East Africa lasted for less than one year. In summer 1940, the Italians launched offensives into Sudan, followed by another one into British Somaliland, which saw a successful capture of Berbera. Heavy terrain and problems with supplies, as well as an uprising in Ethiopia, however, prevented their victory. By July 1941, the last major Italian units in Ethiopia capitulated, and Selassie – together with his son, Amha Selassie I - returned to Addis Ababa (last Italian garrisons gave up only in November 1941).

John Robinson returned to Ethiopia as well – in 1944, now as a Colonel of the US Army Air Force, and leading a team of African American aviators and technicians, to help build new Ethiopian Aviation. The new air arm was in 1945 equipped with two deHavilland D.H.60 Tiger Moths, followed by various other light aircraft. These equipped a flying school that had 75 students by 1946.

|

| One of the first six Ethiopian aircraft ever was this Potez 25 A2, serialled "3" and nick-named "Nesre Makonnen" (Prince Makonnen in Amharic). On delivery, all early Ethiopian aircraft should have been painted in silver-dope, but some were painted in dark green in the mid-1930s. While it is known that national markings were applied on wing surfaces (usually in form of a rectangle in Green, Yellow and Red), this plane wears no other markings but the Lion of Judah - symbol of Imperial Ethiopia. This was applied in Light Brown and Yellow, with Black detailing. (Artwork by Tom Cooper) |

Federation with Eritrea

One of important issues the Ethiopian Emperor had to tackle after the liberation of Ethiopia was to secure Eritrea as a part of his country. Eritrea was colonized by Italians in 1882, but occupied by the British since 1941. Following the WWII, the Moslem League maintained that Eritrea was overwhelmingly Moslem, and objected the rule by the “uncivilized and retrogressive Ethiopians”, searching independence instead. Decades of Italian influence imparted an independent sense on majority of local population, and the “New Eritrea Pro-Italia” as well as the “Italo-Eritrean Association” asked for return of Italian rule. The British denied such wishes as expressed by the “Patrioc Association of the Union of Eritrea and Ethiopia”, which favoured what its name implied, but were also concerned by Soviet stunning request for trusteeship over Tripolitania and Eritrea, expressed at the Potsdam Conference. Therefore, they opted to keep Eritrea under military administration. Soon after the end of WWII they began experiencing troubles on their own while attempting to remain in control of the situation.

The responsibility for order in this territory in the late 1940s rested with the Eritrean Police Field Force (EPFF), assisted in its task by a detachment of Mosquito PR.34s of No.13 Squadron RAF. In April 1948, a detachment of Tempest F.Mk.6s of No.39 Squadron – recently reformed at Nairobi, in Kenya – was sent to Asmara to support ground forces after Shifta nomads from Somaliland made a number of guerrilla attacks. The Tempests were in action late in the year, rocketing rebel camps.

When the UN discussed the future of territory, in 1950, matters became worse, and to better support the EPFF, the British were forced to deploy also the No.1910 Flight, equipped with Auster AOP.6s, from Tripoli to Agordat and Barentu, to fly reconnaissance-, liaison- and supply sorties. Austers also acted as forward controllers, designating targets for Tempests. Brigand light bombers of No.8 Squadron, and Spitfire FR.18s of No.208 Squadron from Aden and Fayid, respectively, were deployed to Asmara in August of the same year, and their detachments remained in Eritrea until summer 1951. Spitfires were subsequently replaced by Meteor FR.Mk.9s, and these were very active in support role later in 1951.

By 1952, it had been decided by the UN that Eritrea should become federated to Ethiopia, and with this decision the British began a pull-out, which was completed in June of the same year with support of several Lancaster GR.1s of No.683 Squadron. The later were based in Hageisa and used for survey work as well. The last British unit to pull out was No.1910 Flight, which departed in September, before joining the No.651 Squadron, then based in Ismailia, in Egypt. Eritrea thus came under full Ethiopian control, and Ethiopian military units deployed around the country, while the IEAF occupied the large airfield at Asmara.

The federation of Ethiopia and Eritrea did not bring any respite. In 1955, in attempt at further development of economy and modernisation of local institutions, Selassie introduced a new national Constitution, establishing Ethiopia as a union of nine provinces and a district of Addis Ababa. The new Constitution was promising huge reforms – even if to many these still appeared as to be slowly obtained. The fact was that the aging Emperor experienced increasing problems in ruling a heterogeneous nation split along ethnic and religious lines. Ethiopian nation, namely, consists of some 40 different tribes, mostly of Semitic or Hamitic origin. The ruling Amharas and Tigreans comprised some 40% of the population and were mostly Coptic Christians. The coastal and lowland peoples of various origins were mostly Moslems. Concentration of power and wealth in the Amharas has aroused jealousy among others, forcing the Emperor to keep power centralized in his hands, even if with strong support of the armed forces, the Church, and the Amhara establishment. Finding no other way out, Selassie could only remain in power by working according the “divide and rule” principle.

Safirs and Fireflies: Early Years of IEAF

Drawing lessons from the Italian invasion, in the immediate post-war period, the Emperor brought Ethiopia into the United Nations (UN) as a founding member, and greatly expanded diplomatic relations. While substituting experienced administrators in place of traditional nobility, Selassie rejected British help whenever the reforms threatened his own personal control over his country: he proved to be a stubborn and determined dictator, but certainly with Ethiopia’s benefit in mind: the Emperor understood that there was a need for the country to modernize in order for him to survive.

One of his early decisions was to establish a dependable tax base. While the nobles of several provinces battled this law, the Emperor managed to make peace with the many Ethiopian ethnic, religions and economic factions through appeasement and compromise, resulting in his country enjoying an unprecedented period of relatively uninterrupted stability and progress. Strengthened with taxes and foreign aid, Haile Selassie was able to spend about 40% of the country’s annual budget on defence and internal security, while diversifying his sources of foreign military assistance. There was no resistance against this development, as simultaneously the Emperor introduced a new judiciary, independent from political preference, and the Ethiopians were in general very proud of their military and independence.

As neither the US nor the UK showed interest in providing serious assistance to the newly-established IEAF, and there were quarrels between Col. Robinson and one of Swedes that worked with the Ethiopian air force, Count Carl-Gustav von Rosen, in early 1946, Emperor Selassie asked Robinson to leave, and appointed Count von Rosen as a new chief of the flying school and commander of the IEAF (von Rosen later became well-known for his actions in Biafra, in 1968; he returned to Ethiopia, in 1977, this time pioneering the use of MFI-15 aircraft for air drops of food supplies during a famine catastrophe; he was killed during an attack of Somali guerrilla). In the spring of 1946, the first group of 20 Swedish instructors arrived in Addis Ababa, launching the actual effort to build up a new air force. Later the same year, the new IEAF was established at Bishoftu (later Debre Zeit), near Addis Ababa, and equipped with five SAAB 91A Safir trainers. A total of 48 aircraft of this type were to follow by the end of the 1960s.

SAAB 91As delivered to Ethiopia wore serials 301 thru 347 (issued according to delivery date, and minus one plane that crashed during delivery flight): 19 were lost in various accidents, but most of the others survived to remain in service as light strikers, used for counterinsurgency operations until 1970 at least, when the rest of the fleet was based in Asmara. At least 18 airframes survived in stored condition until 1999, when 15 of them were purchased by a South African company.

The next Swedish type to enter service was SAAB B17A, a total of 46 of which were delivered (serials of these aircraft were 101 thru 146). A Swedish officer commanded the IEAF until 1962, at which time an Ethiopian assumed command.

|

| Between 1946 and 1966, Sweeden supplied 46 SAAB B17 light bombers to Ethiopia, some of which can be seen on this photograph, while under inspection by Emperor Heile Selassie and Count von Rosen, in 1946. (Photo: SLuM, via Tom Cooper; Artwork by Tom Cooper) |

Meanwhile, in 1950, Ethiopia contacted Fairey Aviation, in the UK, expressing interest to obtain up to 35 Firefly fighter-bombers. After some negotiations, in early 1951, a contract was signed for first nine aircraft, including eight FR.1s and a single T.2 training aircraft. These early Ethiopian Fireflies were refurbished Royal Navy aircraft, and they entered service with the then only operational IEAF unit, the Attack Squadron, from early 1952. In 1954, 14 additional Fireflies, all previously in service with Royal Canadian Navy (nine FR.1s, three T.1s and two T.2s) were purchased as well. It is possible that these were followed by 12 ex-Dutch FR.1s, interest in which was expressed in the same year, but delivery of these was never confirmed.

Despite this significant number of airframes, due to lack of spares, and problems with maintenance, lack of own qualified technicians, as well as having only 12 qualified pilots, the Attack Squadron IEAF never operated more than 16 Fireflies. Most usually, only six were held operational. In fact, most of these aircraft never officially entered service, but were used as sources of spares immediately since their delivery, then the IEAF issued only serials 601 thru 619 to them. Correspondingly, the last operational Fireflies of the Attack Squadron – meanwhile re-designated the No.1 Squadron IEAF – were grounded by 1958, and the unit disbanded. They were briefly returned to service in 1960, when there were tensions with the newly independent Somalia, and the IEAF was ordered to show itself over the border region.

|

| "607" was a Firefly FR.Mk.1 c/n F.5645 and one from the original batch of nine aircraft delivered to Ethiopia directly from the UK. The aircraft is shown here with RAF-style serial, as originally delivered. In later years of their service, Ethiopian Fireflies wore smaller, Swedish-style serials. (Artwork by Tom Cooper) |

|

| Ethiopians have certainly purchased a total of nine Fireflies from the UK and 14 from Canada. It is likely that 16 additional airframes were obtained from the Netherlands, in 1954, but their delivery was never confirmed. This ex-Canadian example was photographed in 1965, already in inoperational condition, at Debre Zeit. The artwork depicts "610", another ex-Canadian Firefly FR.Mk.1, as seen in the mid-1950s. (Photo: Tom Cooper collection; Artwork by Tom Cooper) |

US Military Aid and Involvement in Congo

Simultaneously with Sweden being contracted to help establish the air force, Norway was requested for help in organizing a small coastal navy. Later on, Israeli advisers were to train paratroopers and counterinsurgency units, while an Indian military mission helped established the faculty of the military academy at Harer. In the 1950s, Ethiopian officers attended also military schools in the USA, UK, and Yugoslavia, while an Ethiopian volunteer battalion, consisting of the Imperial Bodyguard and best-known as the “Kagnew Battalion”, was deployed in Korea together with United Nations forces, where they fought with distinction.

Such involvement, and the spread of pan-Arabic wave through the Middle-East, in the early 1950s, resulted in renewed US interest in Ethiopia. In 1953, a US Military Assistance Group was established in Addis Ababa, while the Ethiopians permitted the USA to operate the Kagnew Communication Station, near Asmara. Approximately 300 US soldiers were stationed in the country: while some acted as instructors for Ethiopian military - especially the Ethiopian Army and Air Force - most were manning an important SIGINT/ELINT-base at Kegnew (near Asmara, today in Eritrea), established already back in 1942, at the times said to have been the world’s largest high frequency radio relaying and receiving station.

From 1953 until 1967 equipment and training worth $147 million were supplied from the USA. From these times onwards, the air force personnel was largely US-trained, and strong ties established with Pentagon. The first significant type of US aircraft delivered to Ethiopia was Douglas C-47 Dakota transport, some 13 of which began arriving in 1956. The most important reinforcement for the IEAF at the time were 12 Lockheed T-33As, delivered in 1958, followed by the first batch of 12 North American F-86F Sabres, the first of which arrived later the same year. In the following years, the USA have delivered up to 24 additional Sabres (followed by a first batch of at least eight North American T-28A Nomad trainers as well), then contemporary US reports indicate that no less but four IEAF units were equipped with Sabres, one with Dakotas and one with Nomads by the mid-1960s. The number of T-33As was increased in 1960 as well, when up to 20 Canadian-built RT-33As were obtained by the IEAF.

|

| During the 1960s and in the early 1970s the EtAF was supplied enough Sabres to form a total of five squadrons equipped with them, including the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th FIS, as well as the 5th FBS. The 1st and 2nd FIS were re-equipped with MiG-21s in late 1977, the 4th converted to MiG-17s at the same time, while the 3rd FIS continued operating Sabres well into the 1980s. Note the difference in application of the serial on the nose of this aircraft ("cascaded") in comparission to the Sabre on the artwork above. |

The Ethiopian F-86s were soon to see action – even if not in defence of their homelands. For one year, between late autumn 1961 and October 1962, the EtAF operated a flight of F-86Fs with UN-peacekeepers in Congo. Together with Swedish J-29 "Flying Barrels" (Tunnans) and Indian Canberras, the Ethiopian fighters constituted the UN fighter and attack forces that were involved in a war against Katanga, which - among other - operated some armed Fouga Magisters and T-6s. The UN forces made several attacks against airfields of the Katangese Air Force in Jadotville and Kolwesi, destroying a good part of the "Katanga Air Force". The Ethiopian flight of four F-86Fs was drawn from Nos. 3 and 5 Fighter Squadrons, and was based at the Kamina Base. During the operations in Congo one Ethiopian F-86F was lost for an unknown reason, on 14 October 1962.

The other three F-86Fs returned to Ethiopia eleven days later. The final withdrawal of the Ethiopian flight was kept so secret by the UN headquarter that even the co-located Swedish flight at the base did not know about the withdrawal before the Ethiopian fighters actually took off for their return flight on the 25th October.

|

| Between autumn 1961 and October 1962 the Imperial Ethiopian Air Force operated a flight of F-86Fs, drawn either from the 3rd Fighter Intercept Squadron (FIS) or 5th Fighter Bomber Squadron (FBS)as a part of the UN Air Force in Congo. Together with Swedish Saab J-29 Tunnans and Indian Canberras, the Ethiopian fighters operated against Katangese forces, flying several attacks against the airfields in Jadotville and Kolwesi. During these operations one F-86F was lost to an unknown reason, on 14 October 1962. The remaining four Sabres were returned to Ethiopia eleven days later. (all artworks by Tom Cooper) |

In the early 1960s, it was the Somalia’s growing arsenal and communist arms from Egypt, the Soviet Union and China, that was considered to be posing a serious threat to Ethiopian territorial integrity and which stimulated its further military buildup. Correspondingly, from 1960 until 1964 some 3.000 Imperial Bodyguard personnel – about 10% of the then entire Ethiopian military strength – and a better part of the IEAF, served with the UN peacekeeping force in Congo.

In 1968, some $20 million worth of excess US military stocks had been furnished, including eight Douglas T-28As upgraded to T-28D Trojan standard, and the first four out of eventual ten Northrop F-5A and three F-5B Freedom Fighters. A US military loan enabled the Ethiopians to order four English Electric Canberra B.Mk.52 bombers from the UK. By 1970, the US assistance averaged about $10 million annually and some 25.000 Ethiopian officers and soldiers went through different training courses in the USA. The rate of deliveries was increased after, in October 1970, the ties with the USA were strengthened through new agreements. These included a plan for the USA to equip and train all of the 40.000-man Ethiopian military, in exchange for expansion of the Kagnew Station. The IEAF was subsequently significantly strengthened: already in the same year, an unknown number of additional F-86F Sabres were delivered from Iran, followed by three additional F-5As, in 1974. Meanwhile all the Ethiopian pilots and technicians visited training courses in the USA, while there were plans for establishment of comprehensive workshops in Debre Zeit, which were to enable complex overhauls of all available aircraft in Ethiopia.

Soon afterwards, the Ethiopian Air Force announced plans for acquisition of 17 newly-built Northrop F-5E/F Tiger IIs, 12 Cessna A-37B Dragonflies, and 15 Cessna 310s.

|

| In 1970, the final batch of F-86F Sabres was delivered to Ethiopia - from Iran. Ex-Iranian examples were foremost recognizible by their camouflage, even if the details of this remain unconfirmed, then all the available photographs are black and white. The artwork bellow depicts one of two possible variants, in Dark Grey, Olive and Dark Green. The other possibility is that the Iranians camouflaged their Sabres in the same colours they otherwise used on F-4 Phantoms and F-5 Freedom Fighters, in the early 1970s: these would have been Sand, Special Brown and Dark Green. The photograph above was taken at Debre Zeit, in 1991. (Photo via Tom Cooper; Artwork by Tom Cooper) |

|

| Together with F-86Fs, the USA supplied also T-28 Trojans in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Initially used as trainers, Ethiopian Nomads and Trojans were soon involved in COIN operations against Eritrean rebels, while in service with the 16th Training Squadron. The last Ethiopian T-28s remained operational until 1980, when the unit had also three Cessna 301s and two F-5Bs on strenght. Subsequently, the 16th TAS was completely re-equipped with Soviet-built aircraft, including MiG-21s and L-39ZOs. Note that the lower side of the fuselage and the undersides of this aircraft were probably painted in light blue: this would explain the omission of the black field applied behind the engine exhausts, as usually carried by T-28s. (Artwork by Tom Cooper; Photo: Tom Cooper Collection) |

Bloody Fall of the Solomonic Dynasty

The begining of the end of Imperial rule in Ethiopia came actually already in 1960, when it became clear that the modernizing reforms were too slow for many elements of the population – even if too rapid for others. Although Ethiopia was experiencing further progress, a surprising coup d’etat was attempted by elements within the Imperial Bodyguard (led by Gen. Mengusti Naway and his brother, Garwana Naway), the police chief and some radical intellectuals in Addis Ababa, on 13 December 1960, whilst the Emperor was on a diplomatic mission in Brazil. Lacking internal support, the coup collapsed as soon as Selassie returned to Ethiopia, three days later.

Despite the fact that the Army and the Air Force, as well as the Church, had remained loyal to the Emperor, the incident polarised several elements of the society, and forced Selassie to introduce land reform as well as tax changes. These failed in Parliament, in 1966, because this was controlled by the landowners. As a result, in the following years Ethiopia experienced mounting inflation, corruption and famine.

By the early 1970s, human rights violations and the advanced age of the Emperor added to the problems of his nation. Together with heavy spending for a relatively large professional standing army, and despite the fact that many Ethiopians expressed pride at their armed forces and saw these as a guaranty of national independence, there were increasing student protests that the military was draining resources of the nation. Almost simultaneously, and following a famine of the late 1960s and the early 1970s, the peasants began revolting against their feudal rulers. By the early 1974, Ethiopia – already weakened by years of drought – was full of uproar, strikes and demonstrations: elements of the Army mutinied in January, and several provinces fell into the hands of mutineers, in the following month.

In early June 1974, the mutineers had formed a 120-man Provisional Military Administrative Committee (PMAC) – better known as the “Dergue/Derg”. The PMAC was led by Gen. Anam Amdom, who initially claimed allegiance to the Emperor. Soon enough, however, his supporters began arresting older politicians and nobles connected with the Imperial order, and in July 1974 they issued an official demand for a new constitution.

On 12 September 1974, the Emperor was overthrown in a bloody military coup, during which the Emperor and his most important supporters were all arrested. Eventually, the Derg summarily executed 59 members of the royal family and ministers as well as generals of the royal government, while Haile Selassie died in captivity, in August 1975, as a result of massive torture. Thus ended the Solomonic dynasty that – according to its own legend – ruled over Ethiopia for 3.000 years.

The coup was organized from within and followed by a period of confusion in which several different groups struggled for power, none of which had a clear idea about how to reorganize one of the world’s poorest countries, the vast majority of whose population could neither read nor write. Eventually, the power of feudal Amharian landlords crumbled before the PMAC and two other officers – Lieutenant Colonels Mengistu Haile Mariam and Atnafu Abate - emerged as new Ethiopian leaders following what was actually a new coup, on 23 November 1974, when they wrested power from Gen. Anam Amdom, who was killed together with two former prime ministers and two former defence ministers, while “resisting arrest”.

From this chaos, two predominant groups emerged: the Derg, now comprising 140 members, decided to support Mengistu. The other group of military officers was led by the former Chief of Staff, Brig.Gen. Teferi Bante, who in 1976 replaced Mariam and Abate and became a new head of state.

Political chaos and the bloody struggle were now raging and by the time the revolution – initially supported by majority of Ethiopians – became highly unpopular. Even the sympathy of other African states was alienated. Facing a population that was not interested in ideology, but rather depended on leadership for guide, the Derg split: the majority – which supported Mengistu – embraced Marxism-Leninism, a philosophy of the revolution based on a form of idealistic socialism, which was expected to become interesting to Ethiopian peasants. In their attempt to gain support from the population, the Derg demanded all the land to be nationalised, and set up offices to “politicise” the masses, while establishing a “workers” party – the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Party (EPRP). However, the rest of the movement, foremost Ethiopian democrats, opposed such ideas and supported the former Chief of Staff, Brig.Gen. Teferi Bante. The Ethiopian democrats fought back in Addis Ababa and in north-western Ethiopia (where they were supported from Sudan), and in 1976 forced Mengistu and Abate to back down.

The Derg remained loyal to Mengistu, however, and launched a new coup, on 3 February 1977, culminating in hand-to-hand fighting in the Grand Palace, in Addis Ababa. Bante was killed in a gun battle near his home by rival Derg, and the following day Mengistu’s triumph was hailed even by Cuban leader, Fidel Castro, and subsequently by the USSR. Mengistu and the now ruling EPRP, in turn, very soon came under attack of the Marxist-Leninist group opposed to military government, grouped around a French-educated Marxist Haile Fida – the so-called MEISON - which launched an insurgency. Once again, fighting broke out on the streets of Addis Ababa between MEISON-supporters and the EPRP, resulting in summary executions. By mid-1977, however, Fida was arrested in a murderous campaign of terror launched by Mengistu to establish himself firmly in control.

In May 1977, Mengistu visited Moscow and signed 13 cooperation agreements with the Soviets. He returned to Ethiopia via Tripoli, and Libya later delivered the first shipments of Soviet arms to Mengistu.

|

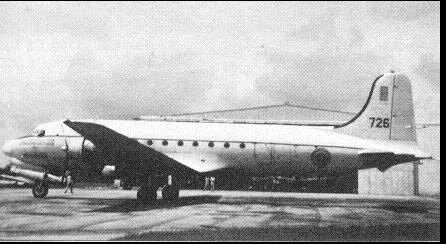

| Ethiopia received three Douglas C-54s (military version of DC-4) from the USA, in 1961. One of these planes was equipped as VIP-transport, and used by Emperor Selassie for his frequent trips abroad. This C-54 was photographed in 1971. (Tom Cooper collection) |

Insurgency in Eritrea

Another of the reasons for the military coup of 1974, was the inability of the Imperial government to solve the problem of Eritrea. Namely, in 1962, the Ethiopian Emperor annexed the territory. The Eritreans wanted their own independent state and were already organized into Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF), founded in Cairo by nationalists who demanded independence and who felt defrauded of it by the British and the United Nations. In time the younger ELF-militants embraced socialist views and eventually split off in 1960, to form the Eritrean People’s Liberation Forces (EPLF). Their new Marxist stance was championed by radical Arab governments in Iraq, Libya, and Syria, as well as by the Palestinian al-Fatah guerrilla movement. By the late 1960s some 22.000 ELF and EPLF fighters were active in Eritrea, mainly operating in the Bara and Tessenei areas, between Om Hajer and Keren. They enjoyed also the support of Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and the Sudan, and inflicted considerable losses on Ethiopian troops.

It was not until 1970, however, that the Ethiopian military reacted in force, and even then only after the Eritreans launched their first larger operations. Several of these developed into considerable battles, that sometimes resulted with as many as 1.000 Ethiopian deaths. As the intensity of EPLF operations increased the Ethiopians were eventually forced to declare the state of emergency in Eritrea and keep a large part of their military stationed there. Initially, the IEAF used only around a dozen of surviving SAAB 91As, based in Asmara, for counterinsurgency (COIN) operations, but in December 1970, these were reinforced by a squadron of F-86s, and a COIN-unit equipped with T-28Ds. Early in 1971, also two Canberras were observed at this airfield while involved in intensive operations against all known EPLF-bases, frequently using napalm.

Little is known about subsequent operations of the IEAF against the Eritrean rebellion, except that by 1974 the EPLF claimed to have shot down seven Ethiopian aircraft in combat. The IEAF indeed should have suffered some losses by the time – few to ground fire and several in flying accident – then it is know that by the time it was left with only six T-28s and less than dozen operational SAABs. Also, in January 1975 Asmara – the second-largest city in Eritrea, with population of 250.000 at that time – nearly fell to an EPLF attack. By late summer 1975 the EPLF was already active inside several other Eritrean cities, and on 13 September 1975 Eritreans attacked the US base in Kagnew, killing nine US servicemen and Ethiopian soldiers.

|

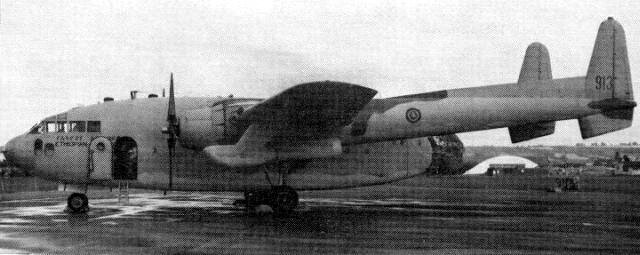

| From 1970, the IEAF began receiving a total of 18 Fairchild C-119 transports. The type saw extensive service during the early stages of the war in Eritrea, and remained operational unitl 1986. (Tom Cooper collection) |

Spread of Rebellion

Despite fierce fighting, by the early 1975 the situation remained fairly static, and the Ethiopian Army had only some 2.500 troops in Eritrea. Most of these were busy preventing the capture of the towns of Ak’ordat and Teseney, which dominated the main route across the Sudanese border. The EPLF meanwhile grew in size to over 30.000 fighters, and developed a capability to deploy its units into Tigray. The fighting soon spread to southern Eritrea and involved other ethnic groups. The Afars, who had a semi-autonomous state ruled from the town of Asahita by Sultan Ali Mireh, resisted attempts by the Derg to impose its rule, while in the nearby Tigray province similar attempts by the PMAC to impose land reforms and increase government control over the lives of the local peasantry resulted in widespread discontent, resulting in an outright revolt, in April 1975. In the course of this uprising the Tigrean Liberation Front (TLF) was established, which was later subsumed into the Tigrean People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), led by Meles Zenawi.

The Derg initially attempted to persuade the Eritrean population to negotiate its differences with the central government, but the Eritreans remained suspicious. When an Eritrean delegation failed to appear on a meeting with the then PMAC chairman, Gen. Teferi Banti, it was clear that the ELF concluded it could do better on the battlefield than on negotiating table.

Assembling an Army of poorly armed and trained conscripts, in May 1976, the Derg launched an offensive in the Asmara area and Ak’ordat corridor, and against the ELF in southern Eritrea. Expecting that the rebels would flee when these units marched into northern Tigray, the Derg forgot that at earlier times the Army could operate with smaller units in the area because these were much better trained and prepared for fighting a COIN war. Without surprise, their rag-tag “army” fell apart when attacked by the Eritreans, and – stalled at Humera – the Derg called off the campaign. Worst yet: by early 1977, most land routes in Eritrea as well as such important population centres like Nakfa, in the very difficult hilly terrain of northern Eritrea, were controlled by the EPLF.

|

| In 1968 Ethiopia purchased four English Electric Canberra B.Mk.52 bombers from the UK (these were refurbished ex-RAF B.Mk.2s). These were 351 (ex-WH638), 352 (ex-WK104), 353 (ex-WJ971), and 354 (ex-WD990). Two were either lost or disabled in accidents by the mid-1970s, one of which suffered heavy damage in a wheels-up landing. Another was flown to an unknown Arab state by a defecting pilot, in 1974. The last remaining example, as well as one of the disabled airframes, were reportedly destroyed by Somali air attacks against Ethiopian airfields, during the Ogaden War, in 1977. (photo: BAe) |

Derg in Trouble

Immediately after the coup in 1974, the new Ethiopian regime repeatedly requested military aid from the USA. The then new administration of president Jimmy Carter turned all requests down and accused Ethiopian military regime of repeated violations of human rights. Although Washington permitted delivery of eight out of 17 F-5Es ordered already before Emperor Selassie was overthrown, as well as some other equipment, in 1976, by the time Mengistu established himself in power his approach on the USSR made any further cooperation with Washington almost impossible.

In March 1977, facing a possible invasion from Somalia, and the obvious loss of control over Eritrea, the Derg announced it had made an agreement with the USSR to obtain Soviet weapons and equipment. In this way, the PMAC expected to have finally found a way around negotiations: with Soviet help, they expected to arm a growing military force, which would first repel the Somali invaders, in the east and the turn its attention to the Eritreans and other internal enemies. Correspondingly, the PMAC soon abandoned reconciliation in favour of a military solution.

Initially, there was no respite, and the situation of the Derg worsened. On 31 January 1977, the EPLF captured Om Hajer, a town on the Eritrean border with Sudan, and then launched an offensive on Tessenei, which fell on 12 April. Within the following months the separatists were even more successful: in August 1977 the EPLF captured Agordat and Barentu. With almost 90% of Eritrea under their control, the rebels have already set up elementary structures of a state, their organisation resembling that of a regular military that had some 12.000 hardened fighters, and a reserve of some 28.000 guerrillas, supported by few M-24 and M-41 tanks (captured from Ethiopian Army), artillery, mortars, and anti-aircraft guns. The EPLF was active also along the whole Red Sea coast, but unable to launch a large attack against the Port of Asseb, in the south.

Then, in July 1977, the Somalis invaded eastern Ethiopia, bringing the entire Ogaden Province under their control and threatening to continue their advance on Dire Dawa and Addis Ababa. For Ethiopia and the Derg, it was vital to maintain control of Eritrea not only in order to use local Red Sea ports, but also to prevent Djibouti from falling into the hands of the Somalis, for without these two territories Ethiopia would be a landlocked state.

|

| In 1974, shortly before Emperor Selassie was overthrown, Iran and the USA donated three additional F-5As to Ethiopia. These aircraft were supplied to Iran in the frame of the Military Assistance Project, so they were US-owned even while in Iranian service. When the Iranians started acquiring more advanced F-5E/Fs instead, a number of their F-5A/Bs was "cascaded" to third parties, including Jordan (which later supplied some of these aircraft to Greece) and South Vietnam. Interestingly, the survivors of ex-Iranian F-5As were sold back by Ethiopia to Iran - in 1985! Note that the original serials of the Imperial Iranian Air Force were hastily removed from this aircraft: they were probably oversprayed by White-Aluminium colour before the new EtAF serial was applied. |

Soviet Airlift

The Somali invasion eventually resulted in the Ogaden War (see separate article). During the initial stages of this conflict the Ethiopian military suffered one setback after the other, losing massive amounts of equipment and stores. Only the Ethiopian Air Force was able to put up effective resistance. However, this was not sufficient for the Ethiopians to be able to re-conquer the lost territories. For such an operation Mengistu needed lots of arms and equipment, preferably acquired at no cost - then by the time his country was bankrupt. Eventually, the Ethiopian dictator requested help from Cuba: working together, Mengistu and Castro devised a plan according to which the Cubans would deploy men and the Soviets material to Ethiopia, re-build the Ethiopian military and then counter-attack the Somalis.

Finding a greater advantage in aligning itself with a large country in the African Horn - namely Ethiopia - Moscow agreed to supply weapons for this enterprise, conditioning these on Ethiopia providing bases for Soviet activities in Africa and the Middle East. For some time the Soviets thus found themselves supplying weapons to two countries that were in war with each other, then they were already selling MiGs and tanks to the Somalia as well.

Their position became untenable, but on 13 November 1977 the Somalis requested the Soviets to leave, terminating the 20-year friendship treaty. Hostile crowds menaced the departing Russians as they clambered aboard aircraft, taking with them hastily gathered belongings. In every sense the departure was undignified. In strategic terms the USSR thus lost the use of the port of Berbera; but, in turn it displaced the Americans in Ethiopia. Clearly, the new situation was suitable for Moscow to state an example on Somalis: a decision was taken to send a strong signal to all the other allies that might be as unreliable. In late 1977 and early 1978, Soviets organized a large air-bridge into Addis Ababa, in which not only 48 MiG-21bis' - together with respective ground equipment and weapons - but also over 200 tanks and armoured vehicles, as well as a total of some 16 Mi-24A helicopter gunships were delivered. Most of this equipment was manned by 2.000 Cuban "instructors" - actually a regular unit of the Cuban Air Force (Fuerza Aérea Revolucionaria = FAR). These reinforcements enabled the Ethiopians and Cubans to deliver a crushing defeat upon Somalis in Ogaden.

First Campaign in Eritrea

The Ethiopian Air Force (EtAF) became active in Eritrea again already before the Ogaden War was concluded. In December 1977, and in January 1978, a squadron of F-86s, few of newly-arrived MiG-21s and – reportedly – even the sole remaining Canberra B.Mk.52 bomber, were in action against the EPLF, hitting five towns between Asmara and Tessenei, again mainly by napalm. Simultaneously, Soviet Navy warships lent crucial naval fire support from the Red Sea to ensure the harbours would not fall to the rebels. These attacks successfully held off the final rebel offensive, enabling the main units of the Ethiopian Army to concentrate on fighting back the Somali invasion in Ogaden.

As soon as major operations in Ogaden were concluded, in mid-March 1978, using Soviet and Ethiopian Air Force (EtAF) transport aircraft, the Derg began shifting troops to Eritrea. During April the whole 2nd Ethiopian Army gathered some 75.000 troops in Asmara and Asseb, equipped with additional numbers of T-55 tanks, BTR-50 and BTR-152 armoured personnel carriers, D-30 122mm and M-46 130mm cannons, and BM-21 multiple rocket launchers, plus hundreds of trucks, as well as extensive amounts of small arms and ammunition. The offensive was launched on 15 May 1978, when four infantry divisions of 12.000 men each, supported by 300 tanks, attacked from Asseb towards north.

The ELF-rebels in southern Eritrea were hardest hit, losing most towns within few weeks. In the north, however, the EPLF simply withdrew to its mountain strongholds around Nakfa. Ak’ordat fell in August 1978, followed by Thio, Edd and Beilul in October, and Keren in November, enabling the Derg to lift the siege of the port of Massawa. The Eritrean forces proved ill-prepared to withstand air raids now launched by the reinforced EtAF and soon all the substantial separatist gains of 1977 had been lost to a military campaign reinforced by Cuban training of Ethiopian troops, Soviet military direction and massive provision of military equipment.

However, this campaign failed to eradicate the EPLF: it even failed to dislodge rebels from Nakfa even in two subsequent offensives, lasting well into December 1978, and January 1979. The EPLF remained stubborn and the Ethiopian offensive increased the cause of Eritrean independence. The ruthless Soviet-backed assaults (Cubans refused to left their troops become involved in the fighting in Eritrea) drove scores of new recruits into EPLF, whose military commander, Ibrahim Affa, could thus count as many as 45.000 fighters in the field by the end of the year. This force had no significant problems to withstand another large Ethiopian offensive – a Soviet-devised attack by 40.000 Ethiopian troops in the Naqfa area, from 16 to 31 July 1979. In this operation the main Ethiopian force advanced from the south, moving overland, while one division was landed on the Red Sea coast in the back of the Eritreans. In major confrontations the Ethiopians suffered a loss of 6.000 troops killed and injured, and the operation was cancelled prematurely.

The final battle of this first Ethiopian campaign in Eritrea took place from 1 to 15 December 1979, in the Nakfa area, and resulted in another repulse of Ethiopian forces. The Eritreans not only caused extensive losses to six army divisions (one or two Ethiopian divisions were virtually annihiliated, suffering more than 15.000 losses), but also captured dozens of tanks and hundreds of vehicles. By mid-January 1980, the government forces retreated to bases near Asmara, and in the following months even the TLF in Tigray made its first major gains, turning this war from one of separatist/liberation character, into a civil war.

Operation Red Star

Unable to defeat the EPLF on the battlefield, the Derg regime responded with a measures to deny the insurgents bases or resources. This turned into a scorched-earth programme, enforced by aerial bombing or artillery shelling of inhabitated villages likely to be used by the insurgents, destruction of crops and livestock, transport and other infrastructures. The aim was to depopulate areas the regime could not hold.

The EtAF – now actively supported by Cuban-flown MiG-23BNs and Mi-24 helicopters – was completely reorganized and flew dozens of larger and smaller air strikes, mainly hitting a number of fortified village complexes known to have been occupied by the EPLF. The Eritreans returned fire from small arms, but obviously lacked proper anti-aircraft weapons, and thus very few losses were suffered by Ethiopian fliers.

With the Ethiopian military temporarily at bay, the EPLF also turned on the ELF: between 28 August and late September 1980, the EPLF drove the ELF from the highlands into the lowland area along the Baraka River, effectively ending its role as a major force in the conflict. In 1981, the remnants of ELF were driven into Sudan, where government forces disarmed its last fighters.

The Ethiopian Army came back in force to Eritrea only in the early 1982, deploying some ten divisions – a total of over 140.000 troops - in preparation for the Operation “Red Star”. The aim of this offensive was to hit the EPLF strongholds of Nakfa and Helhal. Both towns were subjected to unprecedented bombing raids, in which phosphorous and napalm bombs were used extensively. Advancing through a series of ambushes, the Ethiopians managed to penetrate within 10km from Nakfa before being forced to withdraw by determined EPLF counterattacks and up to 20.000 casualties. The Eritreans held out and hit back very hard, in turn flaring-up TPLF operations against government supply bases in Well and Gonder provinces for the first time, thus distracting and stretching Ethiopian resources.

In the end, the Operation "Red Star" failed, with the Ethiopian Army and the Soviets suffering (according to contemporary Eritrean sources) as many as 100.000 casualties. Additionally, the Eritreans, now also armed with SA-7s, claimed an An-26 transport shot down near Asmara, on 14 January 1982, and then began attacking the local airfields by artillery as well.

|

| First MiG-23s were supplied to Ethiopia around 1983, entering service with the 3rd and 4th Squadron. As first they replaced the remaining Sabres and MiG-17s of the 4th Squadron, where also the MiG-23BN shown above was flown, and then the surviving F-86s of the 3rd Squadron. Although not as numerous as MiG-21, the MiG-23BN eventually became the mainstay of the EtAF in the second half of the 1980s and the two units equipped with the type flew several thousands of sorties against Eritrean rebels. |

The Famine War

There was a major dought and famine in Ethiopia, which lasted from 1984 to 1988. As large areas of Ethiopia – foremost Tigray and parts of Eritrea – were hard-hit, the regime was quick to seize upon famine relief, or denial of it, as a weapon to force the population into areas of its control. Relief agencies were denied access into areas of government control, and the EPLF was forced to evacuate a better part of supportive population into southern Sudan. As it was, much famine relief was directly diverted to supply government garrisons and operational units: had it not been for international relief efforts, the Mengistu regime would have likely collapsed.

The extent of government losses in 1982 is reflected in the low level of military activity during the following year. On the other side, later in 1983, the EPLF exploited the situation for preparation of an offensive, in which it deployed captured T-55 tanks, APCs and artillery. The rebels have also obtained their first batch of SA-7 MANPADs, and on 15 January 1984 they shot down the An-12 “1506”, near Tessenei. The rebel attack was launched along the 60km long Nakfa Front, in mid-March 1984, and resulted in overran Army defences, as well as the capture of Karora and Mersa Teklay. The capture of Mersa Teklya – mounted by the first Eritrean mechanized brigade - was a particular blow, then this port was of vital importance as supply base for Ethiopian troops operating in northern Eritrea. When the Ethiopians counterattacked with a fresh infantry division, a mechanized brigade, two tank battalions, four field artillery battalions and six air defence battalions, some 4.000 government troops were killed and 2.500 captured. On 16 April, also the first EtAF MiG-23BN was shot down by anti-aircraft artillery near Nakfa.

The EPLF would not rest. In late March and through April, towns in central and southern Eritrea were attacked and encircled: Alghena, Senafe and Addi Caleh were all captured, together with significant amounts of equipment and stores. Finally, on the night from 20 to 21 May 1984, the rebels attacked the Asmara airfield, where they claimed destruction of no fewer than 32 Ethiopian and Soviet aircraft destroyed, including 16 MiG-21s and MiG-23s, two An-26s, two (Soviet) Il-38s, four other aircraft, and six Mi-8 and Mi-24 helicopters.

The government was slow to respond, even if definitely willing to military crush the Eritrean resistance. Instead of launching a new ground offensive, however, it was the EtAF which was to continue fighting. On 24 and 25 March 1985, formations of Ethiopian Air Force fighters attacked the town of Abi Adi in Tigray, where TPLF members had gathered to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the movement. In a massive attack with high-explosive and cluster bombs, several hundreds civilians were killed and the town severely damaged. The tragedy of Abi Adi subsequently became a rallying cry for the TPLF.

This time, it was on the EPLF to deliver a pay back: during the summer, it captured the town of Barentu, defeating two Ethiopian divisions and a mechanised brigade during a three-day battle, killing over 2.000 troops. Barentu was subsequently lost to an Ethiopian counterattack, but the Eritreans have still shown their ability to defeat large conventional forces on battlefield.

|

| Russian-made bomb, dropped by Ethiopian MiGs against Eritrean positions in the Badme area, in 1984. (via Tom Cooper) |

Sale of F-5s

Due to massive losses and famine, the Derg regime was in 1984 and 1985 forced to do its utmost in order to buy new equipment for its military. The country already received massive loans from the USSR, which it was not able to pay - especially not as its economy was meanwhile completely ruined. When Moscow put Addis Ababa under pressure the EtAF was eventually forced to sell remaining intact F-5As and F-5Es to Iran, in order to pay back some of its debts.

The EtAF was unable to purchase spare parts for this type, and most of remaining airframes were meanwhile in poor condition. While few were kept flyable with help from Socialist Republic of Vietnam (which had inherited a large number of F-5As with the fall of the South Vietnam, in 1975), by the mid-1980s even Hanoi was asking for hard currency in exchange for parts – and the Ethiopians lacked the money. With all the surviving 14 F-5A/Bs and eight F-5Es being in condition that has left no hope for refurbishment, Addis Ababa put them up for sale. Interestingly, this bid attacked no less but three potential customers: Iran, Morocco, and the USA. The Moroccans were foremost interested in F-5Es, but, after inspecting them, they concluded that even a complex overhaul would not be cost effective. The Americans, acting via the CIA, offered the Ethiopians a total of $7 million – in cash, their main interest being to remove US-built aircraft from a Communist-ruled country and the international “black market”. This bid was not interesting for the Derg.

The Iranians, at war with Iraq and under US arms embargo, were far less concerned by possible costs of an overhaul, and found the Ethiopian F-5s a bargain not to be passed on. In late 1985, an Israeli middleman convinced the Commander-in-Chief EtAF, Gen. Fontabelle, to sell him at least four F-5Es, for no less but $68 million, using a British shell company set up for the deal as mediator to the National Iranian Oil Company.

The US officials had no means of stopping this deal, and the four F-5Es – with an average of only 497 flying hours on their airframes, were delivered to Mehrabad. The Iranians, who could not inspect these aircraft before they arrived, were completely disappointed with their condition and refused to accept them, let alone agree to pay for them or buy additional fighters from Ethiopia. There were no maintenance logbooks, less than half of the instruments worked, two F-5Es had their wiring pulled out, and one had a 20mm round jammed in the cannon.

Nevertheless, after additional negotiations, the price was lowered to $34 million, and the Iranians eventually obtained not only the other four F-5E airframes, but also eight F-5As and two F-5Bs. Most of these could not be repaired any more and were broken down to be used as sources of spares for Iranian RF-5As and F-5Bs. But, most of F-5Es were later completely rebuilt by the Iranian Aircraft Industries and returned to service with the Islamic Republic of Iran Air Force (IRIAF). From Iranian point of view, even more important than these aircraft were considerable stocks of spares delivered with them: Iranian technicians were able to return several of battle-damaged F-5Es to operational condition with their help.

The Soviets were satisfied as well, and when the Ethiopians paid at least a part of their loans, Moscow delivered additional MiG-21bis’ and MiG-23BNs to EtAF, as well as few MiG-21RF reconnaissance fighters.

|

| By mid-1980s, the surviving Ethiopian F-5s and F-86s (operated by the 1st and 5th Sqn during the 1960s and 1970s, respectively) were little more than wrecks. In 1985 several F-5As and F-5Es were sold to Iran; the Iranians found the planes for which they paid $68 million in such a poor condition that they wanted to turn them back. |

Preparations for the “Final” Offensive

The year 1986 found the Ethiopian Army and Air Force in the process of training and reorganizing, while new insurgent groups appeared around the country, including the Ethiopian People’s Democratic Movement (EPDM), which cooperated with the TPLF to take Sekota in Wello province, on 6 November. Another group that became active in northern Ethiopia was the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Party (EPRP), which on 27 December attacked a work camp in the Gotam region, overrunning an Army screening force in the process.

Meanwhile, the Soviets – encouraged by the Derg ability to pay back at least parts of the loans – have delivered additional MiG-23BNs and MiG-21bis', as well as few MiG-21RFs to the EtAF. But, on 14 January 1986, the EPLF launched another raid against Asmara AB, hitting especially hard. This time the Eritreans claimed destruction of no less but 42 aircraft and helicopters. Although this claim is almost certainly exaggerated, the Ethiopians suffered terribly from this blow and the EtAF again needed over a year to recover.

For most of 1987, the government forces remained subdued in their garrisons, attempting to reinforce and build up supply depots. The famine continued, and the international relief organizations worked hard to feed populations of Eritrea and Tigray. The Derg continued holding back the relief aid, and on 23 October the EPLF attacked and destroyed a food convoy, citing government practices of using such convoys to cover troop and equipment movements. In the end, both the EPLF and the Derg found themselves busy for what each side claimed would be the “final” offensive: the difference was that the rebels expected to expel no less but 120.000 Ethiopian troops based in Eritrea with only 30.000 own fighters!

Battle of Af Abet

During the late 1980s the Ethiopian Army initiated one "large offensive" against Eritrea after the other. However, none of these produced any lasting results. On the contrary, if successful at all, most of such operations resulted only in a temporary capture of few ruined towns and villages, or opening of communication lines toward the coast of the Red Sea for a limited period of time.

On the other side the EPLF proved not only able to survive, but also highly evasive and capable to hit back. Actually, the Eritreans - supported from many sources outside Ethiopia - grew stronger after every Ethiopian defeat. To the problems of the government in Addis Ababa came also a civil war against TPLF, EPDM, and EPRP, as well as other opposition groups in the country.

The final phase of this war began when in late 1987, the regime had formed a new command, the “Nadew” (Destruction) Command, based in Af Abet, a major logistics and support base for three infantry divisions reinforced with elements of a mechanized division and additional artillery. The offensive was launched in late February 1988, resulting in a series of pitched battles during March. The EPLF was ready: it pre-empted the attack and outmanoeuvered it: between 17 and 19 March, the main body of Ethiopian force was encircled and trapped in a valley near Af Abet, and then subjected to heavy artillery bombardments. By 19 March, the Nadew Command and its three infantry and one mechanized divisions were annihilated, with the loss of 15.000 troops, and the Eritreans captured no less but 50 tanks, 60 artillery pieces, 200 vehicles, and much other equipment intact, together with three Soviet advisors (a fourth was killed in battle). Af Abet was captured on the same evening, and the Eritreans then found themselves on the heels of Ethiopian units that were retreating to Keren.

In order to defend Keren, the Ethiopians were forced to abandon all the towns nearby, but the EPLF then turned and attacked logisitical lines from the port of Massawa to Asmara, and three camps west of the later city, on 21 March. Massawa was also put under artillery bombardment, but in response on 22 March the EtAF fighter-bombers and Mi-24 helicopter gunships attacked the town of Hauzien, in Tigray, with cluster and napalm bombs, killing 360 people, practically all of them civilians. On the following day, the Derg regime imposed the state of emergency in Eritrea and Tigray, and designated the Red Sea coast of Eritrea “prohibited area”, where normal movement by the civilian population was not permitted: all the remaining inhabitants were to be evicted and resettled elsewhere within 15 days. The Ethiopian military was not in condition to support such a blockade, however. By 1 April, EPLF was only 10km from Keren, and its artillery units scored a direct hit at the regional supply depot, which burned for two days. On the next day, the Army withdrew from Agordat and - subsequently – have lost control over large areas of Eritrea. Almost simultaneously, the TPLF captured two towns in Tigray, including two key food distribution centres.

Despite the costly failure, the Derg continued deploying additional units into Eritrea: by 28 May, the regime claimed that the Keren front had been “stabilized”. In fact, it was clear that the regime had lost the initiative. Using the equipment captured at Af Abet, the EPLF was able to outfit several new mechanised and artillery units, while the TPLF easily evaded the Army counteroffensive in Tigray, later capturing a number of additional towns and villages.

|

| Ethiopia purchased a number of SA.316 Alouettes from various sources. The first six apparently arrived from France, in the mid-1960s, while no less but 20 years later some two dozens of Indian-built HAL Chetaks were acquired as well. This example was photographed in Djibouti, in 1991. (Albert Grandolini Collection) |

Final Operations

In 1989, both the EPLF and TPLF initiated offensives with the aim of pre-empting new Army attacks. In Eritrea, the separatists captured huge amounts of arms and supplies during various attacks against convoys and supply depots between Asmara and Massawa, while in Tigray the rebels established control over such a vast area, that they began operations even in Gonder. As of 25 February 1989, Mekelle and Maychew remained the only large towns under government control, while two days later the Army was forced to evacuate Mekelle. Thus, by the early March, the government could not supply the troops of the 2nd Army in Eritrea along the Asmara-Keren corridor any more, instead being forced to use Aseb, near the Djibouti border.

In the middle of these failures, the Derg were hit by an abortive coup attempt against Mengistu and his circle. Organized by senior Army commanders in May 1989, the coup failed, and in reprisal Mengistu ordered execution of all senior officers involved. The EtAF was grounded for weeks afterwards; nevertheless, after an investigation showed that there was no involvement of its elements, it returned to battle.

By the summer 1989, the TPLF launched the operation “Peace in Struggle”, resulting in the capture of Maychew and a large-scale invasion of northern Wello. The military force responsible for this success was now designated the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), which was an umbrella-group for several insurgency movements – most led by Tigreans. After success in Wello, in September the fighting spread into northern Gonder, and on the 30th of the month, the Cuban regime declared its intention to pull the last 2.000 troops out of Ethiopia. The Soviets have had enough as well: openly questioning the wisdom of financing Cuban “internationalist” adventures in Africa, they declared their unwillingness to continue supplying arms, ammunition and equipment. Soon enough, the Ethiopian Army was in total disarray.

In a further series of offensives, Eritreans and Ethiopian opposition successfully cut all remaining Ethiopian corridors to the ports on the Red Sea and destroyed the remaining loyal army divisions. Even the Israeli help for the regime in Addis Ababa - which resulted in delivery of 100 T-55 tanks as well as spare parts and weapons for Ethiopian aircraft, supplied in frame of the Operation "Falacha", in exchange for evacuation of some 30.000 Ethiopian Jews - could not improve the situation of Mengistu’s regime.

Repeated offensives of rebels not only survived massive air attacks of MiG-23BNs and Mi-35s of the EtAF, but - till late 1990 - also destroyed remaining two large Ethiopian ground units. On 15 February 1990, the strategically important port of Massawa was taken by EPLF: without Massawa, the regime in Addis Ababa was cut out from relief aid and arms shipments. On 15 May 1991, final breakthroughs were achieved by EPRDF on Dese and Kmbolcha, where the whole HQ of the Ethiopian 3rd Army was captured. Only couple of days later, on 21 May, Mengistu abandoned Addis Ababa and fled to Zimbabwe (where he was granted asylum and still resides), leaving a caretaker government to face the advancing insurgents.

On the misty morning of 28 May 1991, victorious troops of EPRDF finally entered Addis Ababa. In July 1991, the EPRDF and several other oppositional groups established the Transitional Government of Ethiopia. Thus ended an incredibly brutal, 16-years long civil war in Ethiopia – but also the Eritrean liberation war: Eritrea separated from Ethiopia in 1992, and was recognized as an independent country a year later. The EPRDF and the EPLF, the alliance of which decided the outcome, however, were soon enough to find themselves embroiled in a conflict against each other.

|

| Ethiopian Rebels cheer after capturing the Debre Zeit AB, in May 1991. Note the title "Ethiopian Air Force" applied in English underneath the cockpit of the An-12B in the background - a somewhat unusual practice for an air force heavily dependable on Soviet and Cuban support. (Tom Cooper collection) |

EtAF's Sad Fate

Significantly, the EtAF gave her best during the last days of Mengistu’s regime. In order to defend the remains of the Army and Addis Ababa as long as possible against rebels, its aircraft flew dozens of close support missions. As the rebels were nearing the capital and airfields nearby, the EtAF significantly increased the tempo of operations. Disregarding their own safety, the EtAF pilots flew up to three combat sorties a day, operating aircraft that were barely considered "flyable".

However, when it became clear that their cause was lost Ethiopian pilots chose to left their country together with their planes. No less that 22 different Ethiopian aircraft (one L-39ZO, three MiG-23BN, two An-12B, one Cessna L-19) and 12 helicopters (seven Mi-8, three Mi-35, two Alouette III) were flown to neighbouring countries, mainly to Djibouti.

Most of the airfields were subsequently overrun during final battles, their condition detorriating subsequently even is most of the aircraft, as well as underground depots captured by the Ethiopian and Eritrean rebels survived intact. By late 1991, most of the remaining 36 MiG-23BNs, some 20 MiG-21MFs or any of ten An-12Bs and one An-26 were in poor condition and only aircraft and helicopters flown outside of Ethiopia - and subsequently returned - could have been described as „flyable“.

Nevertheless, the Ethiopians were to re-build their air force - even if it would take them years to do so.

|

| This former Ethiopian MiG-23BN was captured at Asmara, in May 1991. Eritrean markings and even a personal name were applied to the aircraft, but it was never to fly again. (Via Tom Cooper) |

Bibliography

Except for own research and materials kindly supplied by contributors on ACIG.org forum, especially Mr. Tom N. and Mr. Pit Weinert, the following sources of reference were used:

- “CONTINENT ABLAZE: The Insurgency Wars in Africa, 1960 to the Present”, by John W. Turner, Arms and Armour, 1998 (ISBN: 1-85409-128-X)

- "THE WORLD IN CONFLICT; Contemporary Warfare Described and Analysed, War Annual 7", by John Laffin, Brassey's, 1996 (ISBN: 1-85753-196-5)

- "AIR WARS AND AIRCRAFT; A Detailed Record of Air Combat, 1945 to the Present", by Victor Flintham, Arms and Armour Press, 1989

- "FLASHPOINT; At the Front Line of Today's Wars", by Anthony Rogers, Ken Guest and Jim Hooper, Arms and Armour Press, 1994

- “Fairey Firefly Variants”, by William A. Harrison, Wings of Fame, volume 12.

- “Ethiopian Potez 25 A2”, Insignia Magazine, issue six, Blue Rider Publishing

- “Imperial Fireflies: The Long Life of Ethiopian Fairey Fireflies”, by Leif Hellström, AirEnthusiast, volume March/April 2006, No.122.

|

© Copyright 2002-3 by ACIG.org

Top of Page

|

|

|

Latest Central, Eastern, & Southern Africa Database

|

|